|

RONRIDENOUR.COM |

|

RONRIDENOUR.COM |

| Home |

| About Ron Ridenour |

| Articles |

| Themes |

| Poems |

| Short stories |

| Books |

| Links |

| Search |

| Contact |

| Dansk |

| Español |

CUBA AT SEA

by Ron Ridenour

Table of contents

Acknowledgments

Introduction

Chapter One: Seaweed

Chapter Two: Port Santiago de Cuba

Chapter Three: Port Cienfuegos

Chapter Four: Seaweed Retires

Chapter Five: Shark

Chapter Six: Giorita: Sailing to Europe

Chapter Seven: Rose Islands: Return to Cuba

Pictures

(Published by Socialist Resistance, May 1, 2008, London. Written in 1993; revised in 2005).

The events and facts described herein are

real. I have changed some names and mixed some conversations into one

dialogue, but without changing the meaning. On some occasions, terms

for persons appear to be racial, calling someone by his skin color:

black, mulato, white, Chinaman. In Cuban Spanish, these terms are not

derogatory, rather expressions of identification and even of affection.

Sometimes, however, prejudice can be associated with such termonology,

depending on attitude and tone. The reader should not deduce that I

am always in agreement with points of view expressed. I have intended

to paint pictures of the overall society.

I owe gratitude to many Cubans, and one Argentinian, Che Guevara, who

was my midwife into internationalist philosophy and into action against

injustice and imperialism. I also thank the administrators of Caribe,

Mambisa and the Ministry of Transport, and la Dirección de Orientación

de la Revolución, organ of the Communist Party Central Committee

for conceding me permission to navigate with the nation’s ships.

I especially appreciate the officers and crew of the ships: Seaweed,

Shark, Gold Star, Giorita and Rose Islands. These merchant marines accepted

me as a member of their families. They gave me access and space to all

I wished, in order to fulfill my curiosity and assist in my writings.

In large part, the book is inspired by the valiant crew of the small

cargo Hermann:

Captain Diego Sanchez Serrano

Héctor Maura Díaz

Santiago Rodríguez Maya

Héctor González Pagés

Jesús Dole Calzadilla

Jacinto Farnot Camilo

Lino de la Luz Reyes Rosell

Mario Andrés Hidalgo Olívera

Francisco Montalvo Peñalver

Osvaldo Santíago Vega

Annel Bertot Gutiérrez

INTRODUCTION

COMING HOME

SER INTERNACIONALISTA

Es Saldar Nuestra Propia

Deuda con la Humanidad

(To be Internationalist is to settle our own debt with humanity)

This billboard is the first one I remember seeing after

landing in Havana. No better slogan could express my own feelings and

morality than this statement of conscience. I was Home!

It started with a phone call. The year was 1987. I lived in Copenhagen.

"Hello. This is the Cuban embassy. May I help you?" the woman

answered in broken English.

"Yes. I am....and wish to speak with the consul about a trip to Cuba,"

I replied in Spanish.

"Yes. I am the ambassador. Marta Jímenez Martínez at

your service."

I hesitated. I had expected to be answered by a clerk, a secretary, not

the number one representative of their country. That was not what we experience

at any other embassy. I explained my interest in contacting them and was

cordially invited to stop by.

Some background to the phone call is necessary. I had made an agreement

with an El Salvadorian guerrilla commandant to travel with liberation

fighters. I would observe how the people lived and fought, in order to

write a book. I would present their cause to other parts of the world.

In order to complete this mission, I needed to come inside clandestinely.

The government would not grant me—a radical journalist noted in

the empire's intelligence archives—permission to enter the country

and write about the oppression and the dirty war they conducted against

the people. I would fly to Cuba first, then to Mexico and from there inside

El Salvador.

I had never been to Cuba. But it was Cuba’s revolution that

woke me up. The first time I demonstrated was in protest over the

US’s attack on Cuba at the Bay of Pigs. I picketed the Federal

Building in Los Angeles, on April 19, 1961. I joined the Fair Play

for Cuba Committee. I wrote articles in a college underground newspaper

I helped start, "The Raven", about the new government’s

efforts to abolish racism and end poverty. It only seemed natural

that the world's self-declared greatest democracy would aid these

humanitarian practices. Instead, the US government attacked these

very humanitarian policies and even invaded the country in April 1961.

The FBI and CIA began following me and labeled my actions subversive.

Cubans struggle to feed everyone, provide free education and health

care for all, fight for national independence, and the US's reactions

against this goodness led me to understand what my country was actually

about. I was angry and still am.

I came to the embassy with my CV and a copy of my recently published book

on Nicaragua, “Yankee Sandinista”. I hoped that the book would

help identify me and my politics for the Cubans.

It did. The embassy employed five people. Besides the ambassador, there

was her guajiro (1) husband, Luís García., their public

relations representative, Jimmy Santana, his wife Carmen, and a chauffeur

and handyman whose name I can't remember. They all wanted a copy and bought

extras. They weren't just individual employees. They were family. Not

only in blood but in spirit. They accepted me as one of them. They assisted

me with enthusiasm; helped my travel plans and added to them. The Cuban

government had just revealed the identity of 27 ordinary workers, who

had been recruited by the CIA to spy upon their country and sabotage it.

They had accepted the offers and immediately informed their government.

They then became double agents for their people. This became the subject

of a book I would write, "Backfire: The CIA's Biggest Burn".

Jimmy sent copies of "Yankee Sandinistas" to the ministries

of culture and foreign relations, and told me to look up the foreign book

publisher, José Martí Publishers. Maybe they would want

to publish the book and maybe I might write something about the double

agents. He also introduced me to Barbara Dane, an American folk singer

whom I knew indirectly from the Vietnam War days in the USA. She came

to Denmark to perform. Barbara was also the mother of Pablo Menendéz,

who had become a Cuban citizen. He was married to Adría Santana,

a nationally known actress and Jimmy's sister. My wife, Grethe, and I

probably could live with them when we came to Cuba.

One September morning in 1987, Grethe and I landed in Havana's

José Martí airport. Adría and Pablo lived in La Playa

area of Havana. Their plant-covered duplex, slightly shaded from the simmering

sun by palm fronds, overlooked the warm Caribbean splashing on a sandy

beach. We spent an exciting month with them before Grethe returned to

Denmark to her work and I went to El Salvador. In that time, I heard Fidel

Castro "perform" a speech in the parliament. It was my first

of many live speeches by this master orator. I was mesmerized by his folksy

style and his breadth of knowledge about the world. He spoke for four

hours without notes, without water. I could have listened longer.

I was warmly welcomed at Editorial José Martí by the director,

Félix Sautié Mederos, and chief editor, Iván Pérez

Carrión. They had been informed about me and took a copy of "Yankee

Sandinistas" to read. They asked me if I would like to interview

some of the double agents. They wanted to publish a book about them and

what the CIA had set them to do against their country. I could write a

chapter. When I interviewed the first two, a married couple who had worked

for Cuban airlines, I was so impressed with their courage, their dignity

and loyalty that I fell in love with these people.(2)

The first remarkable trait I noticed about Cubans, generally, is their

erect stature and shinning eyes, which emit a sense of self-worth and

equality among all humans. People old enough to have lived under the Batista

dictatorship and neo-colonialism had long forgotten the state of inequality

among humans of different economic and racial status. The young had never

been taught that they must bow down before "superiors." Old

and young alike look everyone in the eyes. And they all take pride in

their personal appearance, in corporal cleanliness and clean clothing.

In my next visit to the publishing house, I was offered a contract to

publish "Yankee Sandinistas" in Spanish. That was good news

but that wasn't all. I reported what I was learning from the double agents

and they asked me to write a book about them myself. I was elated.

It was time for me to take a flight to Mexico. Depending on what occurred

in El Salvador, I might have time to gather more interviews and other

material for the double agents book upon returning to Cuba, en route to

Denmark. I waited about two months in Mexico before receiving word to

enter El Salvador. The most productive and interesting activity I engaged

in while waiting was writing some articles for the English language weekly

magazine, Mexican Review, published by the prestigious left-wing daily

newspaper, "La Jornada." One article, which I did not get to

write, was planned on the film "The Old Gringo" to be shot in

a Mexican province. I had known Jane Fonda in the Los Angeles anti-war

movement, and had interviewed her for "Playboy" magazine (3).

I had also met Burt Lancaster in connection with the black liberation

movement. He was first choice to play the American author, Ambrose Bierce,

who, at age 72, was killed fighting with Mexican revolutionaries, in 1914.

As it turned out, no company would insure Lancaster, due to his age and

health, so Gregory Peck got the role. This delay, and the fact that Mexican

film workers struck, hindered me in doing the piece as I was called to

come into El Salvador.

My first contact with the guerrillas took place smack-dab in front of

a major military base in the capital city. She stepped off a public bus

wearing smart clothing. Young, attractive, she appeared to be a middle

class woman. We strolled across the street from the heavily guarded, walled-in

base.

"I almost got robbed on that bus," she told me with a laugh

in her lyrical voice. "Imagine me, an experienced guerrilla getting

my purse stolen by a bus thief! I discovered his hand just in time. Come,

we’ll get some coffee and talk."

The nature of the warring conflict had changed since a year ago when our

plans were hatched. The Yankees had stepped up their aggressive support

of the puppet regime. There were more pressing needs than the book project,

which would take one or two years before publication. They asked me to

help with cultural solidarity work in Denmark. I was not enthused but

agreed to do one specific project upon my return. Now that I would not

be traveling with them, the next several months were open. I decided to

return to Cuba and complete interviewing and gathering material for the

double agent book.

I returned to Pablo and Adría's home. I set up more interviews

and the Ministry of Interior gave me some access to information on CIA

subversion from their Office of Interest in Havana. Some of the coded

information from both sides were made available. Shortly before I was

to return to Denmark, where I would write the book, the publishing house

and I signed the book contract, and they extended yet another exciting

offer. A job as a "foreign technician," performing editing and

writing functions. The terms of both contracts were generous. I would

be paid 12 pesos per page delivered. This resulted in an average wage

for about 18 months. I would be paid 310 pesos monthly as a contracted

worker, half again the average wage and equivalent to what professional

Cuban editors make. I would also be provided with an apartment where Cubans

live, a ration food and clothing card, which all Cubans have, and other

benefits of socialism, such as free medical care. Grethe could live with

me and our flight to and fro would be paid for. It was an offer of a lifetime.

Just before leaving for Denmark, I heard Pablo's tale of coming to Cuba

and staying. His story coincided with some of my own feelings and experiences.

One difference, however, was that his mother was the first American artist

to break the blockade by conducting a musical tour of Cuba.

"My mother came back ecstatic with Cuba and the revolution,"

he told me. "Barbara felt fully rewarded just from the experience

but when the Ministry of Culture asked how they could repay her, she said:

`I have a son who needs a healthier environment, a place to study music

away from the atmosphere of despair´."

So the Cuban government took in her son. He arrived at the National School

of Arts, in 1966, at age 16. The school was built on the remains of the

plush Havana Country Club, so "exclusive" that the state dictator

had been prohibited entrance. Batista was too dark skinned.

"I was too big for my britches, a conceited little brat," Pablo

told me. "My father gave me the best advice. He said: `You're going

to a country that's been a colony for hundreds of years. People from Spain

and the United States have always told them what to do. So try to keep

your mouth shut and learn their ways´."

Pablo met his wife at the arts school where she was studying theater.

They married young. Adría became a good actress. I saw her perform

a 90-minute monologue before a large audience. It was enthralling to follow

the various characters she played. How can a human being remember so many

words? Adría is a warm, amiable person, zestful and humorous like

the majority of Cubans.

To readers not familiar with Cuba from inside what I here cite from Pablo

may sound like false serendipity. My own later experiences over many years,

however, confirm the essence.

"I feel free in every aspect of my life. A police car comes by and

I never think of them as pigs, as repressors like I did in the United

States. They are our friends, our neighbors, our protectors. There's almost

no crime (4). The few murders are usually crimes of passion. I am free

from drugged-crazed people, child pornography, racism and nazism. There

is total freedom of religion. I do the work I want. And I listen to US

propaganda beamed over radio if I want a laugh.”

Pablo explained internationalism for me in a way that made the billboard

real.

“I’ve sacrificed the need that most people have of identifying

with one country, and gained the sense of being part of two countries,

in fact, the whole world. The minute I’m in any country, I identify

with the problems, hopes and visions of those people. I don’t really

feel marginal but internationalist. Cuba has ten million people cultivating

internationalist feelings. So, everybody here understands me when I play

in a concert.”

Back in Denmark, I began writing the manuscript. Grethe

and I were not doing so well as a couple. She decided not to live with

me in Cuba but would come for extended visits. When I finished the first

draft, Grethe and I traveled to New York City. The US media had published

precious little about the largest infiltration and undermining of CIA

“dirty tricks” in its 40 year history. I tried to get some

media interest in the subject. “Covert Action”, a magazine

dedicated to exposing the counter-intelligence agencies, had published

a comprehensive article about Cuba’s intrepid infiltration. A new

producer, Karen Taylor, at CBS 60-Minutes was interested in the story.

She contacted me. While they were interested, Taylor finally told me that

top management, “won’t go with the story unless we get independent

verification.”

Such “verification” must come from some United States government

or congressional source. The CIA was mute, as they always are, and there

was no gain seen in telling the truth in government or congress. So, “the

story is dead”.

Grethe returned to Denmark and I went on to Cuba. Two publishing house

employees picked me up at the airport. They were most surprised to see

that I had my bicycle with me. This was before the oil shortage and before

Cuba became known for having so many cyclists, especially in Havana. But

I had learned on my first trip that relying on public transportation would

slow me down much more than my energy flow could tolerate . While the

publishing house completed its end of the contract by sending me plane

tickets on time, it had not arranged for a place for me to live. I later

learned that this was normal procedure because the custom is not to rely

on anyone until he or she shows up. But I certainly couldn’t complain

since they arranged for me to stay at a modest hotel used mainly by Cubans

on vacation, Hotel Lincoln, in central Havana. I ended staying there three

months, including one month with Grethe when she came to visit. Accommodations

were fine. The only drawback was the long wait for each meal. My room

and board were paid for so I almost always ate at the hotel. I finished

doing research and a rewrite of the book at the hotel.

I was moved into Cuba’s tallest building, Focsa. This 30-story apartment

building is a triangle which meets on a corner in downtown Havana. It

was built in the 1950s to be a fashionable place for the more wealthy,

but after the revolution Cuban families, middle class and poor, filled

the building. At this time, the occupants were Cubans and foreign technicians

like myself. Most of them were from the Comecon countries.

My editor, Iván Pérez, and the director, approved “Backfire”

and started the publishing process, said to take a year. I met some Cuban

authors who told me not to hold my breath. Most books took from three

to five years to come out. While I waited, I volunteered to work in a

construction brigade building an apartment building. There would be 12

apartments; half would go to employees of the publishing house, which

took responsibility to do some of the work, and the other half would go

to the housing ministry, which assigned the other apartments to people

on a waiting list. I also volunteered to work in agriculture, in a banana

plantation, cultivating vegetables, and chopping sugar cane. Chopping

sugar cane with a machete is one of the toughest jobs in the world: sweltering

hot, back-breaking, and shin-cutting. But I loved doing it. Of course,

I only worked for a week or two at a time. That makes a big difference

in one’s “loving” attitude.

Sautié suggested that I experience Cuba as much as I wished or

could and then write a book about Cuba seen from my eyes. This was a wonderful

idea, one that gave me almost complete freedom. I came up with the idea

of seeing Cuba from both land and sea. I would travel to all the provinces

on bicycle, train, bus, car, plane. I would observe, interview people,

and do some volunteer work to get to know people and their living conditions

better. I would also sail around the island, working and seeing Cuba from

the sea, from seamen’s eyes. I definitely wanted to sail with Captain

Antonio García Urquiola, who had been a double agent and whom I

had interviewed for “Backfire”. Sautié approved the

idea and wrote letters to the Caribe shipping company. But there were

many institutions involved before final approval could be obtained. I

write about paperwork bureaucracy in chapter six; and we meet Captain

Urquiola and his ship, Shark, in chapter five. I got involved in the quest

for approval as well, while I began traveling on land and doing volunteer

work.

I lived like Cubans did. My ration card could buy the same limited goods;

the same scare and cheaply made clothes; the same cigars, rum and beer

“when available”. I had to queue up in the same long slow

lines. My work conditions, wages and benefits were the same. Different

from the norm, however, was that with this assignment I had almost total

say over what I did. So I did a lot of volunteer work, and free lance

journalism. I stashed away 2,000 of the 3,300 pesos I got or would get

for “Backfire”. I could also save a bit from my wage. As a

foreign technician, I did have a couple benefits most Cubans did not.

There were a couple places open only to us where we could buy a decent

meal and drink decent rum “cuando hay” (5). I could receive

and use dollars, which I did when doing free lance reportage. (This possibility

was granted all Cubans in July 1993.) I began to do short broadcasts for

the only non-commercial and somewhat progressive radio network in the

United States, Pacifica Radio. It had five city stations, including one

in Los Angeles, for which I had been a commentator in the 1970s. I called

in news stories from Cuba over a two to three year period. I also wrote

news analysis and features for an English monthly, “South”,

and a piece here or there. (After my time sailing was over, I would become

the English daily “Morning Star” correspondent alongside with

my editorial-translating job at Cuba’s foreign news service, Prensa

Latina.) The few dollars I obtained from these sources went to buy one

or two good bottles of rum a month. I saved the rest for future travel,

for which dollars are essential. When the biggest scandal in Cuba’s

revolutionary history occurred, I called in stories to Pacifica, stories

such as this one, broadcast June 23, 1989:

“The Cuban government announced yesterday preliminary results of

its investigation involving three officials in the army and11 in the Ministry

of Interior. Following tips from Cuban informants and friends of Cuba,

the government discovered that army General Arnaldo Ochoa, Ministry of

Interior General Patricio de la Guardia and his brother, Colonel Antonio

de la Guardia Font, and a score other officers, had been misappropriating

state funds and operating a drug racket for the past three years. The

illegal activities netted the Cubans only $3.5 million.

“Fifteen successful operations were completed involving six tons

of cocaine and a lesser amount of marijuana. The drugs came from the notorious

Pablo Escobar Colombia cartel, and were flown to the Cuban resort in Varadero

using a commercial trade cover under Antonio la Guardia control. The drugs

were then transported to Miami in United States speed boats, the kind

the CIA uses in attacking Cuba...

“The U.S. government began claiming in 1980 that Cuba’s government

and President Fidel Castro are drug traffickers. The Cuban government

responded yesterday that this is the first case of drug trafficking. It

said the criminals were captivated by the dazzling consumer society and

its trinkets, and there was no political motivation.

“The drug scandal is extremely damaging to Cuba. General Ochoa is

only one of two heroes holding the Medal of Honor. He was a key general

in Cuban international operations in Nicaragua, Angola and Ethiopia...”

It was Fidel who initiated the investigation into possible drug smuggling.

This was the first time such criminal activity had occurred since the

revolutionary victory, and was especially painful and embarrassing to

the president and the vast majority of Cubans. It is illegal to grow,

sell and use any intoxicating drug, other than for medical reasons. And

there was almost no drug taking in Cuba, not even marijuana. Fidel discovered,

by reading foreign wire services—a part of his daily routine—that

a former Cuban citizen, Reinaldo Ruíz, claimed, in a court case

in Miami, that he worked with Cuban military officials and drug magnate

Pablo Escobar. He alleged that they carried “cocaine in a light

plane,” with stopovers in Cuba. Within a few months, the government

put its case together and arrested the 14. They all confessed. A trial

was conducted anyway, which is Cuba law. They were found guilty and the

leading four officers and organizers were executed within the month, and

the others were given long prison sentences. The death penalty is rarely

used but for this high crime it was employed, after the supreme court

rendered its affirmation, which is required for death penalty cases, and

after the entire Council of State passed its judgment, also required for

taking lives. This was especially painful to Fidel since he felt so close

to Ochoa.

I was saddened by this turn of events and decided to take a bike trip

to Santa Clara, home of Che Guevara’s museum. The 600-kilometer

round trip also gave me good material for the book I wanted to write about

seeing Cuba from land (still unwritten). I talked with several persons

about the drug case and how the government handled it. People were shocked

and baffled about how such a gruesom crime could be pulled off, given

that the executive government and MININT exercised as much control as

it did and how much the leadership is opposed to drugs.

During the trial, it was revealed that the government had attempted to

dodge the strict US trading blockade by establishing, in 1982, a clandestine

department within MININT—called MC—to quietly implement commercial

operations with US citizens. Cuba sought to acquire medical and laboratory

equipment, medicines and sanitary material, computers and other technological

equipment and parts. MC was the only entity that could get goods transported

into the country without the obligatory customs checks. And that gave

these men the opportunity to cheat. MC had a blank check. As the state

prosecutor said in the trial summary, its ring leader had “the country’s

airways at his disposal; he had the authority to violate all the migration

provisions; he allowed notorious criminals to enter the country and hid

them here; and he was capable of preventing the authorities from taking

action.”

Why were these men given so much authority? Even worse, as a young member

of the Council of State asked, “How is it possible that our society

can produce people who think and act as if they are above it?”

A work colleague had been a translator for Ochoa in Ethiopia. He explained

that some high officials simply have carte blanche power in some circumstances.

Ochoa was already corrupt in 1977. He shopped in Europe for the best made

Mercedes Benz, laced in gold, and demanded that the ship with his car

aboard dock ahead of several others ships set to unload war materials

the country needed in the war with Somalia. Cuba supported Ethiopia without

going into combat. Ochoa and my colleague watched his orders be carried

out, and they got in and drove the car from the dock. Ochoa also made

gifts of cases of Chivas Regal whiskey and expensive pens and watches.

It was impossible to go over Ochoa’s head and complain to higher

authorities. There were none in Ethiopia. My friend questioned how Ochoa

could have risen so high and kept on rising despite his “character

deficiencies” of which the top leaders were then speaking.

The Cuban revolution was constantly instructing people to be righteous

with one another, to stamp out individual greed, and thereby most corruption.

Capitalist societies do not make so much out of these crimes and human

frailties, nor do they inspire collective values. But there were holes

in the Cuban system, and one of them was this broad flexibility in trying

to overcome the strangling blockade. Another compromising element from

the capitalist world, which penetrates Cuba, is international advertizing—including

most films shown—for the consumer society, which so competes so

strongly with collective, sharing values. As Cuban Marxist philosophers

I got to know said: You can’t build true socialism on an island

in a world dominated by its opposite.

One of the new voices of this contradiction, Mikhail Gorbatjov, came to

Cuba that year on a state visit. He was not loved by Cuba’s politically

conscious people, including the leadership. Many thought the CIA had gotten

to him. He was leading the Soviet Union into the world of capitalism,

and it wouldn’t be long before the socialistic system fell apart.

I reported on his trip.

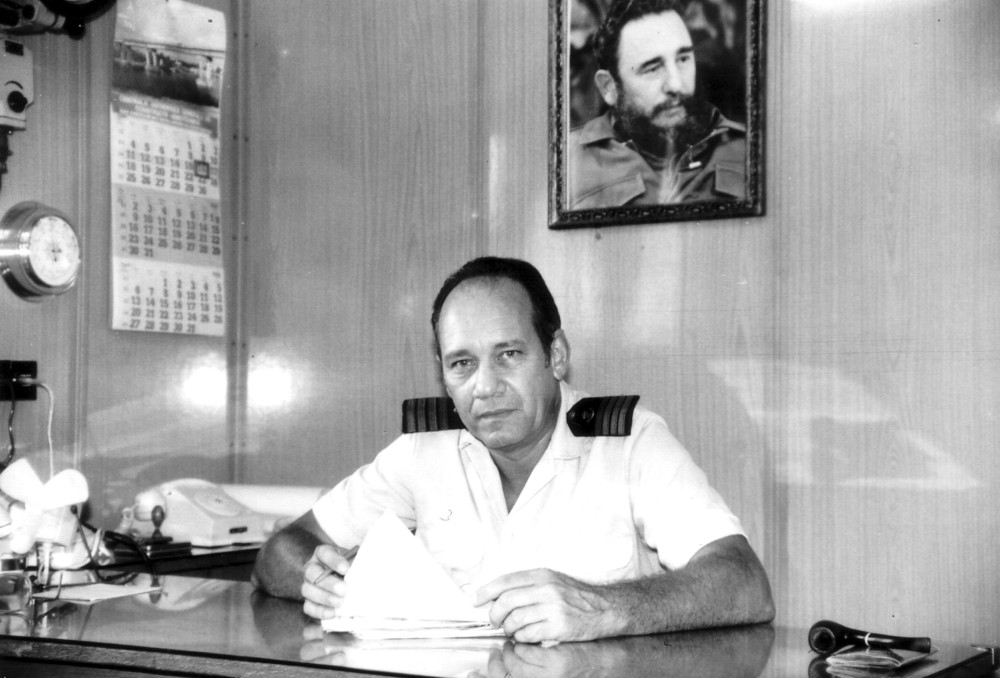

I was granted permission to sail in the summer of 1990. I was told that

this was a first for the Cuban government, allowing a foreigner not in

Comecon to sail on one of their ships. Only Comecon ship technicians had

been allowed. This was to be a unique experience and honor.

I had not sailed much when “Backfire” came out but I had earned

the right to wear the seamen’s tan uniform. I stood before a large

gathering of double agent “subjects”, publishing employees,

media folk and others in my new seamen’s uniform. This was my proudest

moment. I felt I had done something significant to expose the covert warrior-murderers

from the country I had been born in. We held the launching at the Ministry

of Interior’s museum, the most appropriate place given the subject

matter and the collection of material they had on CIA subversion against

their land.

My editor spoke about the book’s contents. I said that I felt part

of their revolution and yearned to do more for it. Then one of the doubles,

Jesús Francisco Díaz (“Dionisio), spoke. I was honored

by his appreciative words, by his and the others’ presence.

The book got many reviews, mainly in Cuba.

A month later, I burned by passport in front of the United States Interests

Section in Havana, in protest against the US invasion of Iraq. It was

a lone action but the media carried it, both nationally and internationally.

I acted, in the first place, out of simple anger and frustration at having

protested one US war after another. Upon reflection, and just before the

event I was staging, I called the media to have my individual action covered,

hoping to inspire others to act in one way or another against the war.

I later heard from people who had seen CNN’s report in Europe, Australia,

China....One of my sons sat in his university dorm and watched, with aggravation,

his father burn the eagle-emblazoned symbol of imperial war. I could no

longer stand to be a citizen of the policeman of the world. I tried other

possibilities to obtain a passport from somewhere—Cuba was not tactically

wise since there would be countries, especially the US, where I could

not travel—but they failed. A year later, I would apply and receive

a temporary US passport, which I had to renew each year, “if you

don’t burn it,” wrote the State Department.

I did not want to return to the United States for many reasons, at least

one was the people. I had come to appreciate Cuban people much more than

any other population I knew.

Cubans are warm and amiable, usually helpful in times of need. They are

humorous, gregarious, generous and gay. Many are self-sacrificing, socially

disciplined. Many criticize and even joke about their system and their

leaders, including Fidel. Few, however, do anything beyond grumbling to

change the circumstances they do not care for. Cubans can also be loud-mouthed,

noisy and inconsiderate. A growing number, are opportunistic and greedy

for consumer goods. One thing everyone enjoys is a good party, which means

dancing to sensuous music. I relate an anecdote, which explains the significance

of this national pastime and Cuba’s folksy Marxism.

An acquaintance, Orlando Licea Díaz, came by my apartment to drink

and discuss the state of human affairs around the time I burned my passport.

He was an erudite Marxist psychologist, who treated asthma patients without

drugs. He invited me to Havana University’s psychology college that

evening where he was to lecture psychologists and students on the psychological

implications of José Martí thoughts. (He said that he had

read the complete works of Martí and Marx several times.) The occasion

was the national celebration of Martí’s birthday.

Upon entering the college, an organizer of the event informed Licea that

the speeches had just been canceled. “We’re partying instead,”

she said, her brilliant eyes smiling rum.

“Great. Let’s go get a drink and dance, Ron,” he said

gleefully and without hesitation.

When he saw my fallen face, he said, “Don’t be sad. There’ll

be another occasion for this lecture. I’d rather drink and dance

than give a speech any day.”

Orlando was handed a large glass of beer, a rarity, and I another. Rum

was abundant so beer was first choice. Many people greeted Orlando while

he surveyed the hall for a pretty woman to dance with. He left me standing

in silence while he danced. When he returned, he said, “I’ve

found a new lover for tonight. Find a woman and let’s dance.”

“You can’t let them just drop the importance of a lecture

on Martí’s day. You spent hours preparing. Canceling serious

subject matters for partying is irresponsible,” I protested.

“You’ll never understand what it is to be a Cuban until you

learn that enjoying life—a woman’s supple arms about you on

a dance floor and a glass of rum—is far more satisfying than academic

regimentation or `fulfilling one’s duty´. Those are Germanic-European

traits which only constrict people, making them uptight and, eventually,

renegades to Marxism. Our marxism (with a small m) is tropical, taking

in the natural course of life. This very fact—that it is more real,

meaning more human—is why it is more solid. There will always be

other times for lectures. Now we party!”

By that time, I had begun sailing. I began to learn from seamen that Licea’s

analysis and appreciation of the Cuban culture is one very important reason

why its socialism has not fallen apart as it has in the rest of the world.

Notes:

1. Small farmer.

2. “Never before have so many moles so completely fooled an

intelligence agency for so long, obtaining volumes of data, spy equipment,

and audio-visual proof of espionage and covert operations against

their nation. The average agent (of these 27 who came out of the cold)

worked clandestinely inside the CIA for 15 years, the longest for

21 years. Never did the stealthy CIA detect one of these double agents.

The CIA suffered such loss of face and real material damage that it

was rendered useless in Cuba, at least for a time.” From Backfire,

page 18.

3. Playboy Interview: Jane Fonda and Tom Hayden, April `74, by Ron

Ridenour and Leroy Aarons.

4. That has changed since 1987-8. Since the fall of Comecon, and increased

tourism, thievery has increased significantly.

5. When there is some.

CHAPTER ONE

SEAWEED

Incipient rays of sun rose over our port bow illuminating

the aqua Atlantic.

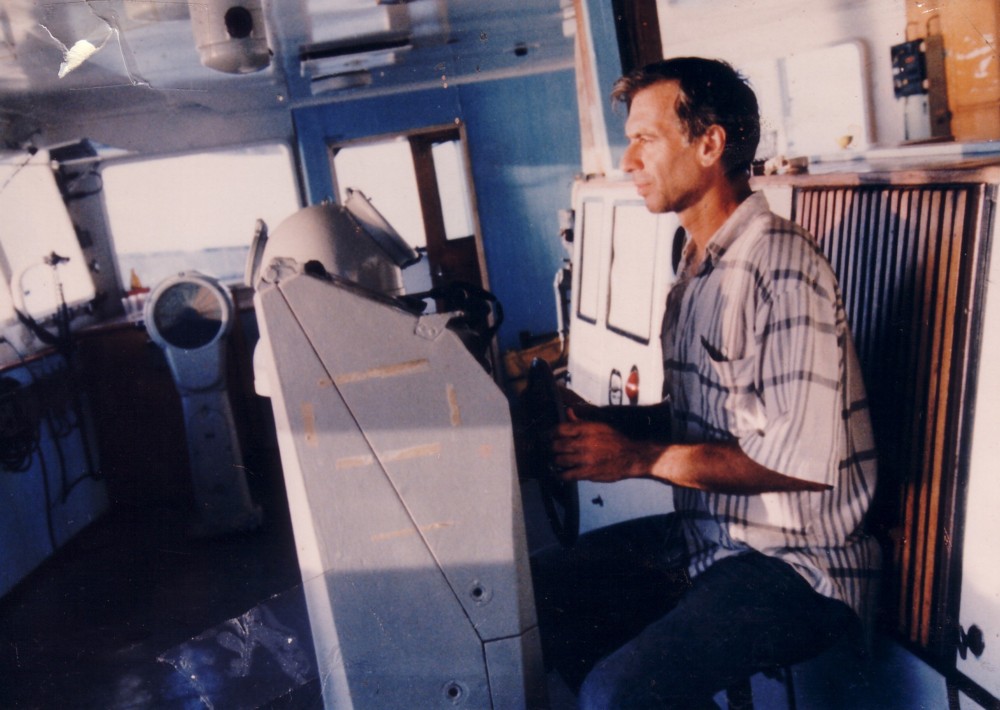

“015 starboard”, commands the first mate, Sigi.

“Aye, 015 degrees starboard,” I reply from the helm as I steer

the Seaweed to a new course.

“Fifteen degrees starboard. Course now 1 5 0 degrees,” I declare

when the compass registers the new bearing. This medium size Soviet-built

tanker is sailing at 12 knots.

“Steady as she goes,” Sigi responds.

At the burst of brightness, the stocky, balding and graying seaman and

I stand side by side in the pilot house. Six decks above water line, we

watch sardine-size flying fish skipping just above the sea. Following

their trajectory, we see the silhouette of a chair-shaped, low mountain.

“There it is, la Silla de Gibara, exclaims a smiling Sigi, “the

first Cuban soil Columbus spied.”

We were passing the Chair of Gibara, jutting alone above the Bay of Bariay

in Holguín province. We were heading southeast toward Santiago

de Cuba where we would load crude oil. On October 27, 1492, Christopher

Columbus and his sailors gazed upon this bay and were the first Europeans

to see Cuba. He described the turquoise bay and verdant coastline, which

he thought was Japan, this way: “This land is the most beautiful

eyes have seen”.

Just two weeks before Columbus had “discovered” America when

he landed on Guanahaní Island, known today as San Salvador Island,

part of the Bahamas. Columbus thought he had found India.

Upon landing in Cuba, Columbus wrote in his log: “I will speak to

the King and see if I can get the gold that I hear he wears.” The

native inhabitants Columbus and his men encountered, the Taínos,

called their island Colba—meaning rock, mountain and cave in their

language. The Spanish wrote it as Cuba. They came to know it as the Key

to the New World. To poets it is the Pearl of the Antilles. The Yankees

eventually followed Columbus´ greedy quest for gold by making Cuba

the Montecarlo of the Caribbean.

Five centuries later, with the commemoration of Columbus´ “discovery”

still fresh, I was sailing around the independent nation hoping to understand

this unique society by inhaling its beauty and dilemmas from the sea.

In the course of two years, I made the bojeo and cabotaje (1), and then

I sailed on Cuban container ships to Europe and return. In all, I sailed

nearly half-a-year. I was the first U.S. citizen to sail on revolutionary

Cuba’s ships. The only non-Cubans to sail were technical workers

from the previous Comecon lands. Cuba has no passenger ships so it took

special permission to be aboard tankers and freighters. I worked with

the men in order to learn and write about Cuba from the sea.

Bariay´s shoreline is nearly barren of life and structures now.

There are only a handful of small, rickety houses, mostly summer shacks

for fishermen who live in nearby Gibara. A simple plaque marks the spot

where Columbus sailed into the narrow bay. I swam in its muddy waters,

feeling historically connected.

When I sailed with Sigi, he was already a veteran seaman of 55 years.

An erudite man, he loved to read and debate about history and historical

figures, such as Columbus.

“Columbus and all his low-breed cohorts were not discoverers of

America. They were simply vulgar invaders. America was already inhabited

by many peoples, who had migrated from Asia. They had social organizations,

economies and cultures. Columbus and his followers were brutal, rapacious

invaders. They came with the cross and the sword to plunder in the name

of civilization. What they left us—we, who were bred here from their

rapings and enslavements, such as my forefathers both from Africa and

native Americans—is their egoism, ambitions and indifference to

others. They left us their social and psychological misery, and half a

millennium later this is still affecting our peoples.”

I was on watch with Sigi. He had shown me how to steer the helm, and instructed

me in the sonar and charting courses, which were beyond my comprehension.

Sigi was mostly a self-taught man, who had worked many jobs in his lifetime

and fought battles during the revolution, although he never managed to

join up with the July 26 Movement. He was always frank with me and a kidder

too. On one of several voyages together he told me what he thought of

life at sea.

“I’ve never liked seamanship, though I’m still a merchant

marine after 25 years. I got into it because it was a Communist party

priority. It was necessary to strengthen our shipping capacity, which

was next to nil before the revolutionary triumph. Many compañeros

(2) took jobs because the country needed them. We were never made to work

where we didn’t want to. We were asked and if we agreed then we

joined up.

“Well, I learned something new, saw many places and people. The

first ship I was shown shocked me it was so huge. I’d never seen

a ship up close and didn’t care much for it but I launched into

this new world from my farming background. After a while, they made me

an instructor. Later, the shipping company gave me a task of investigating

new recruits. I never went into the merchant marine academy but because

of experience at sea, and my own studying, I became an officer. I went

through the ranks to pilot, guiding ships in an out of harbor. Today,

I have my captain’s license but no ship. Continuing as first mate

makes no difference to me; it’s just a job. I’m no romantic.

I love nature but on land. The mountains are what attract me, like la

Silla de Gibara, and especially the Sierra Maestra we will soon be passing.

I grew up alongside those majestic mountains. The sea is dull in comparison.

“Sure, I can feel some pride in that I’m contributing to the

economy, to my country, but I’m only transporting others’

sweat. I don’t produce anything. I don’t sweat. I live a soft

life as an officer. It’s almost a joy ride sailing around the island,

gazing at the shoreline, the sky, the sea. It’s not like the deck

hands who constantly chip away at the endless rust, or the oilers whose

skin is forever greasy black. In my youth, I got more satisfaction as

a volunteer doing hard physical labor than in sailing. But I can’t

regain that sensation by cutting sugar cane for 15 days knowing that I’ve

got such a comfortable life. I make 450 pesos a month basic pay because

of my seniority. The first mate basic pay is 310 pesos. But with bonuses

for sailing, my monthly income is up to 650 pesos, more than triple the

national average wage. But I don’t knuckle down like those who cut

cane. I just can’t feel that pride the sugar cane worker does when

he sees a ship filled with sugar, or with crude oil bought with his labor.

He can look at this ship and say, `There goes my sweat´.”

....

On hands and knees soaking up water from the uneven deck of his berth

is how I first met Captain Miguel Marrón. He wore a frayed T-shirt,

baggy Bermuda shorts, and tennis shoes that most youth hanging out on

the malecón (3) would not be caught wearing. The captain had curly

black hair and sported a bushy black mustache that ended where dimples

began on his bulbous, youthful face.

“Welcome. I’ll be with you in a moment,” he said, wringing

out a rag into a bucket. When he stood, a fresh smile spread over full

cheeks.

“I’m Captain Miguel Marrón, just mopping up a little

leak,” he said, sticking out his wet hand to shake. “The second

mate forgot to turn off the sink faucet when the pump went out. So when

the water flowed again, well, you know, the sink filled up and spilled

all over his room and into my berth. The ship leaks a lot anyway. Afterall,

it’s 20 years old. She’s still running, though. When I get

this sopped up, come back and lets talk. The first mate will take you

to your quarters. We heard you were coming, quite unusual but you are

welcome. How do you pronounce your name?”

“Ron, como en ron.” (4)

“No kidding? Hey, we’ll have to call him Ron Bocoy, right,

first mate.”

I would come to drink a lot of this ordinary rum with the captain and

Sigi Escalona, who came up smiling at me as he took one of my bags. The

captain was smaller than his first mate: too short to make the basketball

team, his favorite sport as a youth, and played the guitar instead. Only

33, the captain had already been a seamen for 15 years.The first mate

was a generation older.

Sigi led me down the hallway, stepping over puddles on the slatted-hardwood

deck.

“Watch your step here,” Sigi warned in rapid-fire command

speech. “We get leaks sometimes from the boat deck where the swimming

pool is. It’s only filled when we’re in the deep so this leak

must originate elsewhere.”

He showed me my quarters, the pilot’s berth, the size of a jail

cell, about 1½ by 2½ meters. There was a narrow bed consisting

of a chewed up piece of foam rubber on boards, a chipped sink that didn’t

work, and a rod with three hangers for clothes. The first mate showed

me his spacious two-room cabin and how to operate his tricky shower and

toilet.

“You can use my bathroom since your sink doesn’t function.

Otherwise, you’d have to go down three staircases to use the crew’s

public showers,” he said, handing me an extra key.

Higher ranking officers have two-room cabins with bathroom. Other officers

have one room, and non-officers sleep two to a room.

The first mate then took me on a cursory tour of the ship.

The upper bridge is not used for anything other than the telegraph antenna.

The lower bridge is a beautiful wooden antique wheel house complete with

a hand-cranked magnetic telephone, which makes an authentic ring. The

phone is used to communicate with the engine room. A modern telephone

hangs on a wall nearby. The wheel house console is made of old hardwood.

The helm operates both manually and automatically. There are two radars

and a variety of equipment foreign to me.

The boat deck contains the swimming pool just long enough to make three

strokes, and gym area with weights and punching bag. Sigi told me that

a deckhand is a former world champion boxer. Over the railings hang four

life boats.

The two poop decks contain the hospital room, nurse quarters, the purser’s

berth and many of the crew’s cabins. The upper or main deck houses

the lowest ranking crew’s cabins. These fellows sweat all the time

as the engine room is one deck below in the hold where the fuel tanks,

water and fuel pumps are also located.

The 9,600-horsepowered engine was built in Poland, a gigantic RD62. The

ship weighs 22,000 tons (displacement), carries 16,500 tons of petroleum

plus crew (deadweight). At 165 meters long, it is considered a large ship—anything

over 145 meters. It measures 21 meters from port to starboard. The Seaweed

is one of Cuba’s three largest petroleum carriers.

Harry, a balding, stout black man in his late 30s, is the chief engineer.

We find him bent over an oily head ring that is four times his weight.

They are equally grease black. The engineers and oilers around him appear

as dwarfs beside the engine. Whatever their natural skin color, they are

all black. Two are greasing bolts one meter long, wise-cracking about

sexual organs and slippery entries.

Harry apologized for the dirt.

“You see, we’re just finishing repairing the head ring. We

lack parts and detergents to properly clean the machinery and us,”

he laughed.

“The Soviet plant that made these ships doesn’t make them

anymore and we have to make our own parts. Our most destacado (5) worker

is our turner. He sweats over the lathe day and night, making everything

from small rings to nuts and bolts and gaskets.”

After a four-course hot meal, I explored the decks on my own. I walked

on the steel gangway, running the length of the main deck from bridge

to forecastle, overlooking a maze of fuel pipelines. The bow stem drew

me to the forward drop point just above the sea. All I could see was pitch

black liquid. I opened a door under the prow that led down staircases

to anchor chains caked in mud. The mud collects when veering in and out

and when the water spray system fails to operate the mud cakes. Later,

I participated in shoveling mud that was nearly petrified.

Directly underneath the bow stem, beside the anchor room, is the forepeak.

It had been used for ballasting but once the ship began carrying only

heavy petroleum products, the six-level deep forepart remained unused.

Constant erosion from wind and salty sea water seeping in had rusted most

of the interior beyond recognition. With a flashlight, I climbed down

until I could see the hull bottom. The wall I touched partly pulverized

in my fingers. I felt as if the decay would crumble and bury me. The image

frightened me. I gained strength upon realizing that three layers of walls

separated the forepeak and me from the sea. Nevertheless, it felt like

the water would suddenly burst through. I scrambled up the winding staircase,

which nearly wedged me in, flung open the hatch and gulped in fresh air.

Benito, the donkeyman, was bent over a fuel pipeline valve. He snapped

his head in my direction at the sound of my gasp.

“Hey man, it’s close quarters down there!”

“You said it,” Benito responded. I hung over a railing while

he explained how the tanker is ballasted and bilged.

The Seaweed doesn’t have a double-bottomed hull where heavy material

can be stored to provide ballast, which produces draft and stability,

so sea water is pumped into four of the 21 fuel-carrying tanks, those

most corroded and unusable for transporting oil. Ballasting is not permitted

until an inspector has determined that no combustible fuel remains in

bilge. Sixty tons of residue oil is usually left over after unloading

the Seaweed. Every ship has a bilge well where water seepage from the

hull’s frames collects and is pumped out once the residue oil is

siphoned into a well in a balanced manner so that the ship does not tilt.

When docked at a refinery, this residue oil bilge is pumped through a

hose to a tank where the fuel settles. When the water is basically cleaned

of oil it is discharged into the harbor. Benito said this is the major

cause of pollution.

The donkeyman took me down into the sweltering fireman’s room where

he regulates the flow of fuel products by opening and closing wheel valves.

The tanks are grouped into fours, each with separate pipes.

“It’s absolutely necessary to assure that the tanks are filled

evenly for proper keel,” he said.

It usually takes 16 hours to fill a tanker with 16,000 tons of crude and

40 hours to unload. Yet it often takes double or more that time due to

numerous delays.

Benito led me down into tank no. 1 on the port side. It is 12 meters deep

and shaped like a wave so that the product moves easily with the ebb and

flow of the ocean. Thick pieces of crust, sediments of oxide, spotted

the iron slabs. Tanks must be cleaned with boiling water and washed with

a chemical cleaner to prevent sediment crusts from forming and contaminating

the product. Indicators show how hot the product is. The temperature should

fluctuate between 40 and 62 degrees centigrade depending on the oil’s

thickness and how much gaseous fumes are present.

I choked from inhaling fumes. Benito said we should have oxygen masks

and an indicator if we were to go further down, otherwise we could become

asphyxiated. I was relieved when he suggested we should ascend from this

black hole. I felt nauseous when he surfaced.

I returned to my quarters to rest and take a swig of rum to rinse out

the foul odors. I felt fortunate that I wasn’t a donkeyman. Sigi

appeared in my doorway. The captain wished to see me in Sigi´s administrative

office. Representatives from the Havana port authority, from customs and

from the shipping company sat around the large oak desk. They handed over

21 copies of the manifesto. Sigi later told me that for many years only

three of the 21 copies were needed. He threw the others away. This waste

is all the more ridiculous considering that since there are so few copying

machines a clerk has to make four sets of carbon copies.

The captain asked where I’d been. When I mentioned the tank I’d

just climbed out of it reminded him of a gruesome story.

“I lost a donkeyman not long ago in Nuevitas harbor. A tube was

stopped up with gas and he went down to fix the problem. He went into

the tank, however, without oxygen equipment. He apparently ignored the

alarm that sounded, indicating the fumes were too thick to enable breathing.

He continued walking through the passageway at the bottom of the tank.

His lungs filled with gas and he conked out. Another seaman realized he

was in trouble and descended to help. But he couldn’t remain down

there without the oxygen apparatus. The men avoid putting it on as it

takes time and is a hassle and, in this case, he was in a hurry. The donkeyman

died and his colleague nearly did as well. Two seamen put on the oxygen

equipment and were able to carry out the second man in time. Luckily,

the nurse hadn’t gone ashore and she revived him.”

......................

We were casting off. I responded joyfully and quickly alongside my new

colleagues to the boatswain and second mate’s orders, heaving in

mooring lines, wrapping the whirling, deadly ropes fast around bitts,

cranking in the two 7.5-ton anchors—and we were veering out.

Two small powerful tug boats pushed us out through the harbor. We glided

past the Morro Castle and its lighthouse. This stone fortress, located

on the eastern corner of the harbor entrance, was in construction for

over a century. It was finally finished in the mid-1700s. The Spaniards

used it as protection against enemies. The lighthouse sits atop a circular

tower 25 meters tall. Its modern light beam rotates every eight minutes

and can be seen from 50 nautical miles.

I was exhilarated as we passed by malecón and the tall apartment

building where I lived, Edificio Focsa, on the 26th floor.

The engine fell silent as the pilot hopped onto a launch alongside our

hull. All ports provide pilots to guide all ships in and out of harbors

as a precaution against accidents, at least in Cuba. The captain took

over command and sounded three long blasts on the horn. At the sound of

the first deafening blast, I ducked and the men laughed. This was the

captain’s signal to the pilot that we were heading out: course 085

degrees to Matanzas.

I walked across the forecastle and climbed to the bow stem. I faced the

vast azure horizon, puffy white clouds and orange-yellow sun. I inhaled

fresh wind and listened to the rippling waves the bulb makes with its

submarine-like nose just under the surface. Here, there is no ear-piercing

human racket, no noxious traffic threatening health and limb. I wished

to be that fantasy animal that can live in the sea and on land, under

the sea and in the air.

Everything was so new and exciting that I slept little the first evenings.

Throughout our voyage, I pitched in on bridge watches, deck maintenance,

and assisted with cleaning the engine room. I accompanied the lone donkeyman

when unloading at electric plants and cement factories, and loading at

refineries. Body discomfortures were soothed by the ever-hypnotizing deep

and the swaying vessel.

Seaman’s life is mostly maintenance and cleaning. A modern ship

is so automated, even these old tankers, that a helmsman is usually not

needed when no close to land and when there is little traffic. So helmsmen

are assigned to scrape and clean with the deckhands. Even the officers,

who conduct four-hour watches, have little to do. They plot courses, making

mathematical calculations on charts and making slight bearing adjustments.

Not even the captain is necessary most of the time. Of course, the captain

is the person to blame when something goes wrong. But his actual duties

are limited. Captain Marrón, however, is an energetic man who participated

in many tasks. The first mate and the chief engineer are the busy men.

The chief’s area of responsibility is always in trouble, and the

first mate must oversee the boatswain and deckhands, the kitchen and chamber

personnel, and the purser. He also takes charge of many financial transactions,

receives the manifesto, the supplies, doles out punishments and, along

with the captain, grants shore leaves. The captain can intervene at any

moment in any area, but rarely does.

I spent a lot of time around Leon on our voyages. The boatswain managed

the deckhands, with whom he worked much of the time, and he was my tutor.

He took time to explain merchant marine training, work conditions and

fleet history.

Cuba hardly had a shipping fleet and no fishing fleet before the revolution.

Then, it only had 14 cargo ships—the largest was 7000 tons—and

three small tankers which transported molasses. Cuba relied on United

States vessels for shipping. In the first five years of revolution, the

socialist government bought a score of ships. By the 1990s, it owned 100

general cargo ships, including container vessels, 17 tankers and a couple

dozen large fishing vessels that process fish at sea. Cuban waters are

home for many varieties of delectable fish and shellfish. Local fishermen

catch large quantities of queen lobsters while long distance fishermen

bring in the largest quantities of fish for export. Fish products comprise

a sizable amount of national income in hard currency. Few natives, however,

eat fish. This is both a question of habit and offer. The ministry of

internal commerce makes little effort to offer fish to the public. Refrigeration,

among other things, is a problem.

Cuba has bought ships not only from the Comecon countries and China but

also from Japan, Canada, England, Spain and the Nordic countries. Its

tankers are usually limited to transporting petroleum products refined

at Havana and Santiago de Cuba to national ports and nearby countries,

making the coasting trade. A handful of tankers transport chemical acids

and molasses. Most of the ships specialize in transporting one product

because cleaning the tanks of crude black petroleum derivatives is costly

and time consuming. A few ships carry lighter petroleum products, such

as: gas, kerosene and naphtha. The entire fuel fleet has a total capacity

of only 100,000 tons, hardly what the largest modern tanker can carry.

The former Soviet used to send 300 ships—with a deadweight of 80,000

tons or more—with fuel to Cuba annually, up to 13 millions tons

of oil in 1989. A score of Cuban ports receive petroleum products, another

score handle general cargo, sugar, cement and minerals. Only a few ports

are reserved for fishing and naval usage.

Before the revolution there was no formal education for seamen. Since

the 1970s, the usual way to become a seaman is to take the six month course

at the Seaman´s College, which is open to all over 17 years of age.

The training, like all education in Cuba, is free. Here one learns the

trade’s terminology, how to tie knots, to walk on ship and swim

in the sea, how to put out fires and what to do if an accident occurs

or if the ship sinks. The student also learns how the ship functions in

a broad sense, and then specializes in one of the departments: deck, engine

room, donkeyman, kitchen and chambers, and communications. To become a

bridge officer, engineer or electrician one has to pass five years of

instruction at the Naval Academy. Prerequisites for captaincy conform

with universal standards.

General conditions for merchant marines is superior to most all other

jobs.Wages are above the national average, from a low of 141 for service

workers and 161 pesos for seaman up to 355 for captain (1990s scale).

Everyone receives additional bonuses of 5 to 15% when sailing plus extra

pay for seniority, hazardous duty, long trips and when work quotas are

met. Food is varied, plentiful and free. When traveling abroad warm clothing

is provided to all. Every 90 days workers are entitled to 25 days rest

plus 10 days vacation. There are complaints, however, that the 90 days

sailing time is often extended without consultation. When one’s

leave is due, the company must provide transportation to return the sailor

home.

A nurse of doctor is always aboard cabotaje trips; and always a doctor,

usually with a nurse, on long distance voyages. Until the 1990s, ships

also employed a politico, a political officer or social-education director.

He or she offered information and political briefings to the crew, gave

Communist party advice to the captain, and arranged recreation and sports

activities.

Tankers provide important services for society but the work is monotonous,

risky and stressful. One lives in a potentially dangerous environment.

One must always be cautious not to cause fires and explosions, not to

solder or produce sharp blows in many places, not to smoke where forbidden.

One must be disciplined and calm. Though most sailors do not appear insecure

or tense, asthma and hypertension among the most common illnesses treated.

Leon was healthy in body and mind, in part, because of his seaman philosophy.

A ship is a small town, a world unto itself. If you like that world everything

is fine, or at least tolerable; if you don’t, then you feel sad

and become sick. Leon put it this way: “You must love your ship

and the sea. The ship is your house; the captain your father; the crew

your family; the sea your world.”

......

Leon was born in a port town, Puerto Padre, in Las Tunas province, in

1944. Raised by his fisherman father, Leon’s first job was with

the state fishing fleet. Then came military service and fighting counter-revolutionaries

in the Escambray mountains. Afterwards, he returned to sea, to tug boats

and fishing. But he got tired of the state fishing operation and transferred

to dry cargo ships and later to tankers.

Leon joined the Union de Juventud Comunista/UTC (Young Communist League)

in 1968, a year after he was promoted to boatswain. In 1974, he joined

the Communist party and is now the party’s organizing secretary

aboard the Seaweed. One third of the crew are CP or UTC members.

“We communists try to help the entire crew develop as workers and

persons. We discuss the work and production plans in our party nucleus,

and offer our opinions to the ship’s leadership. But the ship is

run by the captain. Whether he is a member of the party or not, his word

is law. The party has no special rights on ships. I ask the captain what

his plan is and how the party can help. I never tell him anything. Nor

does the party `spy´ on the captain or any sailor. If it did, it

wouldn’t serve anyone, it wouldn’t work. If the captain does

something wrong or gives an order that seems incorrect, I might object,

but I’ll do what he says. If he turns out to be wrong, then I, like

any crew member, can accuse him before a company disciplinary hearing.

“We are one big family aboard ship. We take care of each other.

We have a routine, a set time to work, to eat, to relax and to sleep.

This helps us stay healthy and organized. This way our ship sails smoothly.

It is not just a job but a whole way of life. Here, you lose connection

with daily events in the streets, in your home on land. But when you see

the news on television or hear it on radio, for instance, that a factory

did not make its production goals because its fuel was delivered when

it should have been, you know you are a vital part of society. You know

that many plants and people depend upon your work. It gets in your blood.

If it doesn’t, you’d better get the hell off the ship.”

The life of merchant marines can also be uncertain, Leon adds. One never

knows when the job will be done, when the voyage will end or take a new

direction. One night stands and longer sexual affairs at various ports

can crop up not only for the pleasure of it but as relief from stress.

This occurs to women sailors as well, although they must not mention it

around men.

The boatswain’s blond eyebrows pinched together momentarily and

then relaxed.

“I love the motion of the ocean, the solitary life. If I have a

problem I take it here and talk to myself. The sea helps me form a life,

helps me appreciate my family and friends, helps me meditate, to measure

the worth of life. When you think you love or respect someone and you

imagine him or her while you are meditating with the ocean’s rhythm,

you realize if you are lying to yourself or not. When you reach port you

are certain what counts and what doesn’t.”

......

On course to Matanzas, I picked and hammered at the interminable

rust. Sometimes an electric pick hammer was used for the thickest crusts.

The perpetual hammering jolted my brain. I had no ear protective device

as there were only enough for half the deckhands. Most of the engine crew

wore protection; they needed it most.

On hands and knees, we banged and scraped old paint and oxides. We brushed

specks with a hard wire brush and then swept the deck clean. We would

now rub in oil to prevent dirt from collecting on the deck. Then we would

apply the anti-corrosive paint, then two coats of thick paint. When we

were about to apply the first coat, seaman Luis took the pail of rust

and cast it overboard.

“What are you doing!” I said astonished. “The sea is

our mother and you are shitting in her,” I continued indignantly.

Startled at my outburst, Luis snorted.

“She’s my mother too. But we always throw rust overboard,

just like the cook throws garbage overboard, and the entire crew throws

their wastes overboard too. What else are we supposed to do with it?”

“You could store it in pails and barrels or special containers,

and take it to garbage dumps ashore,” I suggested.

“There is no system for that. All the ships would have to have thousands

of containers. It would be too difficult and expensive,” Luis replied,

soberly.

“Well, maybe we lack proper respect for our mother,” I moralized.

“She is getting sick from all these industrial wastes discarded

in her.”

“At least we don’t throw junk overboard when we’re in

harbor, not usually anyway,” Luis rationalized.

“That doesn’t solve the problem. The junk moves anywhere the

currents take it, and kills plant and animal life. It contaminates the

fish. They get sick and we get sick,” I replied.

“Ah, the sea is big; it can hold it all,” Luis retorted, petulantly.

Other deckhands listened to us argue, smiling paternalistically at my

self-righteous tone. I had stepped out of bounds. Cubans usually avoid

biting confrontations.

I shook my head sadly, realizing I could not change their casual notion

towards ecology. The entire international maritime industry is contaminated

with this listless attitude. Cuba was no different. I stopped lecturing.

Luis was sensitive today, anyway. The first mate had just handed him four

puestos (6) for failing to return on time from leave in Havana. Luis had

checked at the company’s operations office to find out when the

Seaweed was to sail. Learning that she would depart later than was posted

aboard the ship’s blackboard, he didn’t bother to arrive until

she was casting off. He barely made it aboard by jumping from a shuttle

launch as she was departing. Sigi did not see the situation the same as

had Luis. A captain’s orders takes precedence over an operational

delay. So Luis must stay aboard ship during the next four port stops.

That could mean a month without seeing his wife, or girl friends.

The ship’s nurse stood by a railing on the poop deck overhead. I

climbed up to speak with her about her job and ecology. The large woman

explained that her principle task, besides treatment for minor wounds,

was preventive medicine.

“Preventive medicine! Do you think it is healthy for us to routinely

dump all sorts of wastes into the sea?” I asked, a bit too forcefully.

She looked at me hesitantly.

“Well,” she drawled, “it may not be optimal but its

what everybody does all over the world. My job is limited. I look after

life aboard ship. I can’t worry about the world’s ecology.

That is for governments to manage. It’s chow time; let’s eat.”

I watched sadly as one more bucket of rust rushed into the sea. A school

of dolphins swam past. I doubted that their home is really large enough

to harbor them and mankind’s garbage.

After chow we approached the new container terminal at Matanzas. A Russian

tanker was dwarfed by a 220,000-ton Iraqi tanker. It was so large it could

not dock. The Iraqi vessel unloaded its crude directly into tanks of Cuban

ships, which would transport the petroleum to Havana´s refinery

for processing.

Two tugs boats pulled alongside and pushed us to port. I helped deckhands

on the bow moor the ship. The heaving line, known as jibalay in pigeon

Spanish, is a thin rope with a heavy ball attached to one end. It is thrown

lasso style to a dock worker who then pulls it hand over hand until the

mooring line reaches a bollard around which he wraps the loop, thus fastening

the ship to the dock. On deck, the anchors were dropped and the 80-meter

long, steel chains clanged out from the windlass. Deckhands, aft and forward,

unwrapped and wrapped lines around bitts and capstans, careful to obtain

just the right tension, and the ship gradually swung into its berth. If

the tension is too loose, a line could snap during the tightening process

and would sling about like lightning. If the rope strikes a person, it

will take off that body part it hits.Tremendous energy is required to

properly wrap the lines around the cylindrical posts. Men run about in

order to keep the proper timing and tension. Many mooring lines are needed

to secure a ship: headline, forward breast, forward spring, two abeams,

sternline, aft breast and aft spring. I held onto the thick rope with

gloved hands and heaved behind three sailors. We fastened double lines

around four bitts for extra stability so that the engine could be tested

while docked. The last step in mooring is to secure a flat, square piece

of rubber or scrap metal over the holes where mooring lines pass through.

This prevents rats from scrambling aboard.

Our job completed, we washed, changed clothes and heartily consumed the

caldo, malanga, congri, (7) roast pork and sweetened coconut bits. This

is a typical meal, although most Cubans in the 1990s were not often able

to eat so much. Sailors get two hot meals with meat and two heavy soups,

plus two snacks, on a daily basis.

Some men went ashore; others were on watch duty; a few

of us gazed at the Russian tanker, which prompted a discussion about the

failed perestroika. An oiler made an observation I came to hear often.

“Gorbachev did the work that the entire CIA couldn’t accomplish.

Gorbachev got his ass greased for Bush’s midnight snack and ran

out on us. I wouldn’t put it past the US government to take advantage

of the weak-kneed Russian government to conduct another blockade around

us, like what they are doing to Iraq.”

Sigi was worried too.

“If perestroika had been applied like it was conceived, and if it

had come earlier, it might have been of benefit for socialism, for the

Soviet Union and for all socialist countries. But it palled completely.

I have often compared what Gorbachev wrote and said with what he did.

It didn’t match. I think he fooled people so that he could have

a free hand to act for capitalism. I’ve marveled at Gorbachev´s

ingeniousness. I think he was an agent for imperialism. He said he wanted

to eliminate errors made during socialism but he betrayed socialism. He

renounced its positive tradition of solidarity with the Third World. He

gave the Yankees a free hand to make war in Iraq. He allowed the unification

of Germany, and the disappearance of a socialist counterbalance. He even

agreed with Bush to withdraw all Soviet troops from out land, thus leaving

the Yankee troops on our soil at Guantánamo. It is most disheartening.”

On a later short voyage from Las Tunas to Havana—in which I completed

the bojeo on the Gold Star—I had a similar conversation with the

ship’s captain, Humberto Arangueren and the port director, René

Marrero.

“The big difference with Cuba and the other previous socialist states

is that we began our history by resisting invaders,” Marrero said.

“Most of the other socialist states did not undergo a revolution

and thus did not have a revolutionary conscious people. After our 1959

revolutionary victory, we finally achieved our independence for the first

time. And we never gave the Soviet Union one inch of territory, although

we became too dependent on them economically, to be sure. But, unlike

other supposed socialist states, we remained our own country. Our big

mistake was not to take the necessary measures to be self-sufficient in

food production. We’ve begun to do so now. If only we started a

generation ago, we’d be sailing smoothly now.”

“Why didn’t you start a generation ago,” I asked.

“It’s difficult to know, but no one could foresee then that

the socialist world would crumble.”

“Perhaps,” I said, “but many leftists in the world,

and Che, could see that what the Soviets were doing couldn’t last.

Maybe most Cubans didn’t see it coming because there is little debate

or criticism in the media and in the educational and political process.

Without honest evaluation of facts and divergent ideas, one can’t

understand reality sufficiently in order to plan ahead intelligently.

Moreover, no nation can be truly self-sufficient if it relies on others

for its food.”

“It’s painful to say,” Captain Arangueren interjected,

“but we became accustomed to what we received so easily from the

Soviet Union. We had all we needed, really. It’s like father always

providing food for his children. They don’t worry about getting

their own, and you never think about your father dying. But he did. And

we weren’t prepared. It was a great error, a great error. But I

believe the measures we’re now taking, including in the maritime

industry, will pull us through.”

......................

At midnight, I conducted bridge watch with Arturo, the second mate, and

Manso, the helmsman. We were on a course of 130 degrees toward Caibarién,

the helmsman’s home town. Manso grew up in a family of fishermen

and merchant marines. His father was a cargo ship captain.

We were passing the Archipiélago de Sabana, one of Cuba’s

five large bodies of water sprinkled with islets and cays. It runs the

entire distance from Matanzas to Caibarién in Santa Clara province.

A star fell over the bow and into a still, flat sea. La mar fuerza cero,

(8) declared Manso softly.

A ship was crossing our bow about six miles ahead traveling at our speed,

13.8 knots.

“There’s a ship ahead seeming to make circles,” Manso

informed Arturo, who immediately looked up from checking a chart to study

the radar for the ship’s bearing, speed and distance from our ship.

Six miles separation is the minimum distance considered safe between two

ships sailing at perpendicular angles, and the ship passed without any

violation of safety rules. Arturo then measured the time lapse between

beams emanating from a nearby lighthouse, in order to identify it and

thus be certain of our location. He checked the chart and the chronometer

to compare our plotted direction with where we actually were in time and

space.

“Dead center on course,” proclaimed Arturo.