|

RONRIDENOUR.COM |

|

RONRIDENOUR.COM |

| Home |

| About Ron Ridenour |

| Articles |

| Themes |

| Poems |

| Short stories |

| Books |

| Links |

| Search |

| Contact |

| Dansk |

| Español |

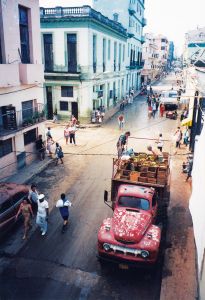

Volunteer Farm Work in Cuba 1992-2006

[January 2007, series of five published by Axisoflogic.com]

Showing up for work!

1992-1993

At the crack of dawn one humid July morning, I mounted my trusty iron

horse and pedaled off to La Julia in Batabano municipality, 50 kilometers

south of my Havana residence. I was on my way to participate in what

Che called that ”special atmosphere” of collective volunteer

labor.

“To build communism, you must build new man, as well as the

economic base...the instrument for mobilizing the masses ... must be

moral in character ... Work must cease being what it still is today,

a compulsory social obligation, and be transformed into a social duty

... Our goal is that the individual feels the need to perform voluntary

labor out of internal motivation, as well as because of the special

atmosphere that exists.” (1)

A “Special Period” was declared by the State soon after

the collapse of European state socialism. Cubans lost 63% of their foodstuffs,

previously imported from Comecon trade partners. They also lost 85%

of export income including oil-for-sugar barter trade.

Cuba’s leaders designated plan alimentario (food plan)

as priority number one, alongside tourism. The state emphasizes becoming

self-sufficient in many areas. Everybody’s belt had to be tightened.

After cycling without stop for two hours, a sign marked GIA-2 appeared

on the flat horizon saturated with banana plants and vegetable crops.

The camp looked like others I had just passed: white-painted, one-story

concrete dormitory buildings neatly arranged in rows. Shrubs, flowers

and garden vegetables grew between the buildings. In the distance, I

could just make out the sea where I had sailed past Batabano on petroleum

runs.

GIA-2’s director, Oscar Geerken, a handsome man in his mid-40s,

led me to his cubicle where I’d be staying. It had four, two-tiered

bunk beds, thin foam rubber mattresses and pillows. Two ventilators

whirled overhead to cool the room and chase away persistent mosquitoes,

Cuba’s only dangerous animal as Fidel was fond of saying.

“We built this camp ourselves with help from local constructors”,

proudly proclaimed the mustachioed Oscar, “and we did it in just

29 days.”

Geerken was a chemistry teacher and school administrator, who had come

here with the original 120 founders, in November 1990. He, like the

others, would get his job back following two years of volunteer work,

or even before if he quit earlier.

When I first arrived to work, in early 1992, there were 220 workers

at Colonel Mambi Juan Delgado Contingent. Commonly called GIA-2, it

received its official name after an officer who had rescued the cadaver

of hero Antonio Maceo, a leading Cuban general killed in battle, in

1896.

At Home in GIA-2

The cubicles are divided by gender. In the front of cubicles housing

50 women was a space used for the polyclinic attended by a permanent

nurse or doctor. Most of the ailments are minor: machete cuts, colds,

asthma and hypertension. A new sugar cane-based pharmaceutical pill,

called PPG, is administered to regulate cholesterol for those with hypertension.

Its “magical” properties include the purported side-effect

of stimulating sexual drives, for which there is scant need in Cuba.

A recreation building across the courtyard is divided into two large

rooms. One has two television sets at opposite ends so that viewers

can choose between the nation?s two channels. The other room affords

space for a ping-pong table and card tables for dominos, checkers and

chess. These tables are cleared away for Saturday night dances. The

recreation hall is brightly dotted with art works painted by volunteer

worker-artists. Another building, quite long and divided by gender,

contains toilets, wash basins and showers. Although the toilets are

flushable, and even though there is a permanent cleaning staff, a putrid

odor constantly lingers.

Corrugated laundry sinks are attached to the bathroom facilities. It

is almost always the women who do the washing for male lovers or friends.

Because they do the washing women go to the front of the chow line.

The only complaint one hears about gender arrangements is that contingent

policy makes it difficult to copulate because the sexes cannot be together

in cubicles. Violators can be fired.

" We can't afford to have domestic relations spill over into collective

quarrels, or cause people to get up late for work. Some would object

on moral grounds as well. But people find ways to link up," Geerken

smilingly explained from first-hand experience.

We entered the brightly decorated cafeteria and were handed metal trays

heaped with moros y cristianos (beans and rice, named after dark-skinned

Moors and white Christians), steaming bean soup, hot dogs, a sweet made

from freshly picked egg plant, and soda. The menu on the wall announced

cod fish for dinner. Cod is caught by Cuban fishermen in far away colder

waters. Breakfast is usually the same: hot milk and coffee with a piece

of hard bread. Breakfast and dinner are free of charge; lunch costs

.50 centavos.

Goin' Bananas

After a two-hour lunch break, Geerken introduced me to the head of finca

13, the 73-hectare banana plantation. Oscar Rodriguez is a history and

philosophy professor. The brigade assigned to initiate the banana plantation

elected him their chief because he was the only man here raised on a

farm who also had some knowledge of growing bananas.

By working in the plantation during several visits over a four-year

period, I learned some of the mysteries of growing this beautiful, tasty

and utilitarian fruit. It is also one of the few fruits to which the

stomach takes easily when in uproar. The plant itself can be used for

many things: food for work animals, protection from sunshine, for roasting

meat; and its fibers are used for textiles.

Entering the mature plantation in the early morning dew is a venerate

experience. The shadowy silence and fresh moisture embraces and comforts.

Under the tall fruit banana and shorter burro banana trees, the sun

does not penetrate to human height and fronds protect one from rain.

All is green and tranquil.

My adrenalin churns as I scout for the marked bananas. A technician

has designated which ones are ready to cut. Some trees have fallen from

the force of the last cyclone. A combination of heavy winds and the

nematodos virus had wiped out a section of the plantation. A few cords

were snapped and some overhead wires were broken but GIA-2 got off lucky

this time. Cutting banana bunches is heavy work yet also fun. One holds

the bunch with one arm and swings the short machete at the top of the

trunk with the other. When the bunch falls onto one?s chest, one swings

at the vine just above the bunch to cut off the tree top. The worker

then carries the 30 to 40-kilo bunch to the "street" (a series

of rows) where the oxen cart passes by. Another man will load them and

cover the fruit with fronds to protect them from the hot sun. Sometimes

the bunch is dumped gently into the cart by the cutter if the oxen are

passing by.

Dripping sap stains clothes and the body. Yet the same plant produces

a watery liquid that washes away body stains. At the day?s end, we dip

our fingers in the liquid where trunk layers turn brown. These juices

clean the sap stains.

Oxen, mud, critters and steel wheels: The cyclone had left the earth

muddy and the oxen yoke got stuck in a dip, and the cart couldn't budge.

The driver was working Contrario and Asabache. He couldn't convince

them to budge despite using the flimsy whip. He called for Nelson. When

the tall young man arrived, he set his jaws tight and struck one beast's

ticklish ribs with his fist. Contrario (obstinate) stepped sidewise.

Nelson wanted him to step forward. He slapped Contrario's rear with

the flat of his machete and threw dirt into the animal's mouth--"To

dry the foam and get rid of his agitation by giving him a new one,"

Nelson explained. The beast plunged forward and with Asabache pulled

the heavy cart out of the mud.

In the 1980s Cuba had more tractors per acre than California for food production. But after the collapse of the Soviet Union and under the heel of the U.S. embargo they lacked the petroleum to use them. Cuba heroically responded by growing crops with the use of oxen as part of their appropriate technology program. They had about 50,000 teams left in 1990. By the year 2000, they had over 400,000 teams of oxen plying the land.

After we cut the marked bunches, our team was set to dig new holes

for the chopos (pods of young plants). The rains had left the earth

so muddy it was difficult to hoe. My clothes and body quickly caked

with mud. It rained again and we slid and slipped. After a while the

rain and mud didn't matter but the biting insects did: mosquitoes, ants

and gegen, a gnat-like fly that bites likes horseflies. Once the green

plant is cut, the chopos smell like fresh rubber and attract a tiny

black ant whose bite stings for minutes.

I walked alongside a yoke, careful not to get too close to the oxen's

thick hooves, catching the pods from a female worker, who threw them

from the slow-moving cart. I placed the chopos on the earth two meters

apart. After seeding a dozen rows, we hoed and topped the pods with

loose soil.

Working with women can either slow down production, due to inevitable

flirtation and different gender capacities, or sometimes speed it up,

because the men like to show off and women often sing stimulating songs.

Love songs and swinging hips induce faster work motions as a distraction

to rising passions.

The next day, I sat beside a tractor driver. I was shocked to watch

a dozen mature banana trees get rudely eliminated by the monster as

its steel assortments ruined bunches or felled plants because of the

driver's reckless driving. This experience made it clear to me that

using oxen and hand-work with machetes is more respectful of nature?s

gifts, although perhaps not as economically efficient since hand-work

is much slower than machinery.

I got off this mechanical brute and cut dried trunk leaves with the

short-bladed machete. Once the inner sides are exposed, one can often

find a tiny frog therein. It is a slimy but harmless, cute creature

that incomprehensively frightens most Cuban women and some men.

Bounty and good banana health

Cuba still employs chemical sprays against plant diseases even under

the special period limitations and with heightened ecological awareness.

Sigatoka (sugar cane rust) spreads so rapidly and is so lethal to crops

that airplanes are used to spray nauseating, imported chemicals. Fumigating

new sprouts of weeds growing close to plants is a constant, tedious

task of brigaders, who apply the Belgian-made Monsanto herbicide from

a tank carried on their backs. The instructions call for extreme caution

and use of goggles, though this is generally ignored.

The natural fungus, verticullium lecani, is used against the ruinous

white fly, which attacks fronds, although many farmers still use the

ancient method of mixing tobacco leaf leftovers with water as a harmless

but time-consuming way of combating the white fly. Another fungus, trichoderma,

is used effectively against injurious fungi in other crops. Even the

lion ant is helpful against some plagues. It will be a long time, however,

before biological methods will replace the need for the unfavorable

chemicals to control farmers' many menaces.

Finca 13 is comprised of 150,000 "silk" banana trees surrounded

by two rows of the protective, sturdy burro plants, whose squatty banana

is cooked green in a variety of dishes: boiled, mashed, roasted and

fried. The silk banana is eaten raw, as are other types. The special

period's food plan stresses planting a few types of bananas least susceptible

to plagues.

Once the banana plant matures, it sprouts a large purple bud popularly

known as a "tit". The tit weighs half-a-kilo and is half-a-meter

long. They droop heavily from pendulous stalks. Tit bracts easily roll

back to expose a glossy silk-like lining. Beneath each bract lay overlapping

rows of cream-colored, unisex flowers from which emanates a perfume

fragrance. First to appear on the tit's corded spike is several rows

of female flowers, whose ovaries develop into "hands" of bananas.

" We used to cultivate only one crop a year," Rodriguez told

me, "and our banana production was way under demand. There were

so many plagues, so many resources and so much attention required that

we never caught up with demand. With new technology and increased manpower

we'll soon have enough bananas to eat.

" Just imagine, if we'd been planting enough of our own food all

along we wouldn't have such significant economic problems now that the

Comecon is gone. We made a grave error relying on foreign friends to

feed us, but we're correcting that now."

The new technology being employed includes the Israel-developed microjet

irrigation system. Israel uses this for growing citrus fruits in deserts,

and Cuba is importing the system from France for use in banana plantations

as well as citrus crops. The microjet is one of Fidel's pet projects,

along with PPG pill production for export. He predicted that within

a few years of installing the effective watering system yields would

quadruple and bunches would produce a score of hands weighing up to

70 kilos. After two years of microjet usage, yields had increased and

bunches had grown in size and weight but the objective was still off

mark, and the system is expensive.

Another day I was cultivating vegetables with Gildy, a dynamic 22-year

old former factory worker. She had suddenly found herself out of work

when the radio assembly plant where she worked reduced its labor force.

She went to the municipal labor office and they suggested she try the

farm contingent.

" This is secure work and I get double my previous pay. The food

is better than you get in the city on rations, and all the essentials

are provided. And I feel useful, so it still appeals to me after a year,"

Gildy told me.

" Because of our natural amiability, we have no real social problems

here, other than a bit of jealousy from time to time. But that happens

wherever men and women live and work together."

Near quitting time workers rushed excitedly from the field shouting,

"Fidel is coming! Fidel! Vive Fidel!"

Three black Mercedes limosines sped by. A blue mini-van filled with

armed security men drove at either end. Fidel didn't stop this time;

he had visited GIA-2 recently.

Down with Cuban Soul on Saturday Night!

Women had decorated the recreation hall and prepared snacks of salad,

toasted bread and fried burro bananas. Some men had gone off to find

draught rum at the state liquor counter-store. As expected, the store

was out of the national alcohol. Tonight was special, so the men scurried

about to find black market rum at double the price. Contingent Colonel

Mambi Juan Delgado's own band, the "Microjets", was performing

for the first time.

Muscular banana workers dressed up in spick and span white clothing

beat out sensual rhythms on congos, drums, trumpets, vibes, organ and

clave sticks as other brigaders gyrated to salsa and humped to son (Cuban

soul) music. The women were sexily decked out in revealing clothing

and inexpensive but sparkling jewelry. Some of them could have been

models or Tropicana dancers.

We listened to music and danced until past midnight. No matter the late

hour or the amount of booze, everyone would be up at 05:50 AM. Awakened

by music blaring out from the camp radio, we would all fall out for

the morning assembly (matutino), partaking in participatory democracy

before our labor began.

"A contingent without a matutino is not a contingent," wrote

the Cuban journalist, Clemente, who once worked there when I did.

The leadership informs workers at these daily assemblies what agricultural

developments are taking place. The previous day's work is quickly evaluated,

and the current day's tasks are outlined. The floor is then opened for

questions and comments. At the end of this interchange, lasting between

15 and 30 minutes, the destacados (distinguished workers),

chosen by all workers, are announced. Bonuses or vacations are awarded

every few months to those most frequently chosen destacado.

At this matutino, Geerken explained that he'd been to the Ministry of

Internal Commerce to see about sorely needed work clothing. Many workers

had holes in their work shoes not to mention tattered shirts and pants.

A few did not even have work shoes. Socks were a rarity.

" We know that most textile factories are shut down and the ministry

has few reserves. They told me they'd soon be distributing some shoes

but they couldn't say when."

A cloudy look fell over most faces yet no one spoke. They knew this

was the truth and there was nothing that could be said. But Big Roberto

spoke up after the general production chief, Jose Aguero, said that

Brigade 8 was behind in planting potatoes and would have to speed up.

"Give us more hands," Big Roberto retorted. "Finca 13

is overstaffed and we are undermanned."

No one contradicted this assessment so Aguero shifted part of the banana

personnel over to potatoes for a while. Someone held up a tooth brush

and a towel. "Did anyone leave these in the bathroom?" A man

raised his hand and gladly took the hard-to-replace items. It was time

to go to work.

Scarcity and its Cousin Crime

Crime increases wherever food scarcity exists. Cuba is no different.

With the generalized scracity of goods and special period cutbacks,

morality becomes shaky. Crime had soared so alarmingly that the Communist

party took the issue up publicly. Stealing had become so common, especially

food meant for common distribution, that stealing was not considered

as such but simply seen as "resolving a problem".

It had become customary for passer-byers to take what they could from

the fields, and many farm workers did likewise. After the first year

of the special period, the vice-minister of agriculture reported that

an estimated two million chickens had been robbed from aviaries, double

the number the previous year.

Guards were now posted in farm areas. In the beginning only two guards

patrolled GIA-2 at night. After crops began to disappear and the first

ox was slaughtered and carted away, the number of guards increased to

16. They took turns patrolling around the clock. Production was affected

with this loss of 16 workers. At first, guards carried loaded rifles

or shotguns but after the first thief was shot by a working guard, authorities

took the bullets away. The shooting death occurred in another province

and the local people believed it was unnecessary punishment. The fact

that local and national authorities listened and responded in kind was

an encouraging sign for democracy and humanistic tolerance about punishment.

Armed or not, guards could not keep banana bunches from disappearing

from our plantation. Every once in a while, clothing and precious soap

were taken too. The worst theft was that of a brand new Chinese bicycle.

Pedro had left his bicycle in his cubicle without locking it. When he

returned from working the tomato field it was missing. Geerken suspected

someone and confronted that person. At first denying responsibility,

the suspect admitted his deed after Geerken threatened to summon the

police to check his family's house where, in fact, he had stashed the

bicycle. Our disciplinary committee voted unanimously for his expulsion.

A report of his deed was written, which would follow him to his next

place of employment. The committee voted not to recommend a trial, which

could have resulted in a jail sentence.

Feeding Havana

Personnel turnover was another destabilizing problem. Of the original

120 founders, nearly 100 stuck out their two year commitment. But those

who came after the initial period were not so consequential. Several

hundred volunteers had come and gone in the second two-year period.

Nevertheless, general performance and production levels were among the

very best of these volunteer collectives. Aguero tried to make sense

of this apparent contradiction.

"The majority leave simply because the work is too hard and the

sun too hot. A few leave because they would prefer another task than

the one they were assigned. Some leave because of illness or family

troubles. Married couples split up because so much time away from one

another is a drain on the relationship. My own marriage is on rocky

terrain.

"A few leave because they weren't real volunteers," Aguero

continued. "Not many, but some have been encouraged to come because

they had no other work or this was a condition for parole from prison.

About 100 have been booted out because of bad behavior: excessive drunkedness

leading to anti-social behavior; slapping women about and similar acts

of violence; a couple cases of thievery, and a few for having sexual

relations in cubicles. Leadership here is strict but not rigid or formalistic.

We are strict enough to get the job done and win a few `best´

awards."

Batabano's state vegetable and fruit farms are a microcosm of government-run

collective farms the nation over. In an interview with the party-appointed

municipal agricultural director, Aldolfo Montalvo, he told me frankly

how farming had been developing.

Before the special period and the food plan this agricultural zone was

cultivated by 105 permanent farm workers, supplemented, like all other

farms, by school children, who are hardly proficient. Now, we've got

more hands than we ever dreamed. The permanent force is 150 and they

have received a wage hike. They are re-enforced by about 2,000 volunteers

who commit themselves for from 15 days to two years. These are mainly

adults who come from cities. At peak times, we are sent soldiers as

extra hands. Most soldiers assist in agricultural throughout the nation

and the army has its own farms, which produce most of the soliders'

food.

"Like all other areas we have received more fertilizers, herbicides,

farm equipment, and oxen in substitute for less petroleum."

The area's 200 caballerias (8000 hectares) yield has doubled

to 20,000 tons in this new period. GIA-2 with 900 hectares of land is

more than ten percent of the land in use.

"There is no doubt that we are spending more money than is cost

efficient for the increased production. Nor do I foresee a break-even

point in the near future. However, right now we are most concerned about

feeding the entire city and province of Havana."

Notes:

1. Excerpted from speeches Che gave to workers as the Minister of Industry,

taken from "Che Guevara and the Cuban Revolution", seven volumes

published in Havana by Editorial Ministerio de Azucar.

FOOD DISTRIBUTION

Second in series

[Editor's Note: This is the second installment in Ron Ridenour's

wonderful series on his volunteer farm work in Cuba after the fall of

the Soviet Union which left Cuba in dire economic straits. The response

of the Cuban people to their devastating losses at that time are not

only creative and resourceful, but downright exemplary and inspiring.

Les Blough, Editor]

________________________________________

Batabano's Farm production director, Aldolfo Montalvo, and Contingente

Col. Mambi Juan Delgado overall leader biggest headache in achieving

the huge and new task of feeding much of the province of Havana was

distributing the harvests before they wasted away.

I attended the first national assembly meeting in Havana concerning

the progress of plan alimentario, in which distribution was discussed.

Candido Palmero, the chief of Contingente Blas Roca, one of the most

distinguished contingents, delivered a report to the nation's leaders.

Palmero had recently been named head of all the new agricultural contingents.

He told the deputies that the contingents could guarantee the production

goals for next year but there was one major problem. The large calloused-handed

man paused. He and Fidel looked at one other from across the large hall.

The president gestured for Candido to continue.

" What I can't guarantee is that you will eat all the harvested

crops, because we don't have our own trucks to distribute the goods."

Palmero now spoke to a hushed assembly. "We recommend that farm-workers

should have the responsibility, the authority and the means to do the

entire job, from breaking ground to delivery."

Fidel enthusiastically agreed and so did the deputies, who decided that

each state farm would get its own transportation to delivery production.

This would first be tried in Havana's fifteen municipalities. The bureaucratic

distribution system is a centralized one in which all harvests are transported

to central markets, called Acopios, where they are unloaded. Smaller

distribution trucks are then assigned to load the products again and

distribute them to smaller neighborhood markets. This process is almost

never carried out in a timely fashion. The double work of loading and

unloading, and transporting results in constant losses of edible foods.

In 1993, Defense Minister Raul Castro said that the Farming Production

Cooperatives (CPA) were six times more effective than the state collectives.

CPAs had been formed in the 1960s as cooperatives of private farmers,

owners and usufructaries. Members share in profits from sales and can

hire day laborers at peak times. State farm workers received fix wages

regardless of production quantity or quality. Ra?l proposed that most

of the granjas, which held 80% of agricultural lands (four million hectares),

be transformed into new usufruct cooperatives with some CPA benefits.

The government then established a new cooperative structure, Basic Unit

of Co-operative Production-UBPC, "to simulate greater production".

Key features of the new UBPC decree-law 142 are:

• Co-operative members have full use of the land without owning

it?unlike CPAs where co-operators are full owners.

• UBPC members are owners of production, like the CPAs, in that

they are free to work and organize as they choose but must sell their

produce to the state at agreed upon prices.

• Farm equipment, seed, fertilizer, herbicides, pesticides, petroleum,

parts, irrigation and other supplies are provided by the state on credit.

• Labor is paid, in part, by profit-sharing. The state advances

an average monthly wage and capital to get started. Credit is repaid

from the sale of harvests.

• UBPCs must be cost-accountable, profitable enterprises.

• UBPC members elect their leadership, which is subject to recall.

Worker leadership represents all workers before state managers and state

investors.

These changes were introduced after state leaders had studied the CPAs

relationships to their land and their style of work. They learned that

not only are CPAs better producers, in quantity and quality, than state

collectivists but that these workers are more pleased with their work

and daily lives. They also earn more money than collectivists. State

leaders did not say, however, why they had decided not to sell the land

to UBPC users. This does not coincide with the conclusion that a major

incentive for CPA co-operators is their ownership status. But the man-on-the-street

knows that the party leadership hopes that with a more stimulating work

life, and thus improvements in the food economy, Cubans will learn that

private ownership of land is not necessary for a decent economic life.

Once the UBPCs established themselves, most contingent members returned

to their waiting city jobs. Some did remain on the restructured farms.

They were joined by traditional collective farm workers and other country

folk from eastern provinces.

Two years following the decision to change the production structure,

the entrenched bureaucracy had not adequately changed the transportation

system.

During one of my volunteer periods at GIA-2, I encouraged Cuban reporter

Clemente to ride on a distribution truck and describe his experience

in an article. His newspaper printed portions of his article. What went

unpublished was quite revealing. Clemente had written that some bananas

were sold illegally on route and at the market place. About 1,400 pounds

of the 30 to 32,000 pounds of bananas loaded at the field never reached

the targeted consumers. Some 50 warehouse workers remained sitting on

their hands for a long time after we pulled up with the truck, delaying

the unloading process. Nor did Clemente's observation appear that there

were about 2,000 pounds lost to "scale discrepancies".

My own random investigation into wastes at my local market revealed

128 boxes of rotten mangoes (5,760 pounds) out of a total of 553 boxes

delivered two days before. The store manager and accountant told me

this was "normal". They said they can reject overripe or bruised

produce but they can't physically check each box upon arrival. "Furthermore,

who wins if the markets don't accept produce they can't sell?"

asked the accountant rhetorically. "If the trucker has to return

the produce it just goes to waste anyway."

Back on the farm

" Guajiro" country music whines atonally like the

hillbilly twang of the un-neighborly northern neighbor. Radio Rebelde

plays it full blast at 05:50 a.m. Though the singing is shrill and the

guitar sounds squeaky, the message is aimed at stirring awake.

Edgardo slowly lifts an acrylic blanket from his face and swings his

legs over the lower bunk bed. He lumbers out into the star-lit morning

and over to his wife's cubicle. Guillermina embraces him and hands over

the empty beer cans for him to fill with their breakfast--a mixture

of powdered milk and cereal--at the dining hall.

The middle-aged couple had left their grown children in Santiago de

Cuba to seek new horizons. Edgardo Rochet had a maintenance job at a

secondary school where Guillermina Montero was a school cook. They had

been here six months when I met them, in 1994.

The Col. Mambi Juan Delgado Contingent had been recently converted into

the new type state farm cooperative, a UBC, and renamed Jose A. Fernandez

cooperative, after a local martyr. Most people still referred to it

by its original collective nomenclature: GIA-2. The workers still till

over 850 hectares of bananas, potatoes, sweet potatoes, cabbage and

tomatoes, but they now plant 26 hectares in vegetables for co-operative

consumption, hoping this will be one incentive to keep people here for

good.

The new state cooperatives no longer rely on volunteers and they have

reorganized many of the previous collectives to approximate the agricultural

production co-operatives (CPA), which traditionally have comprised twelve

percent of farm land. The state collectives had comprised 80 percent

of farm land; some of this land is being converted into UBPCs.

The rest of Cuba's cultivated land, eight percent, is owned by 75,000

small private farmers. Most had formed the National Association of Small

Farmers/ANAP in the mid-60s. Private farmers can own no more than 65

hectares. No land can be sold privately but can be passed down if the

inheritors have lived on the land before the owner's death.

Ever since the special period began, the nation's leadership had been

criticizing the state organized collectives for under-producing. Both

private and cooperative farms, and the army itself, have been better

farmers, and the quality and diversity of food grown has also been better.

Plowing

This Cuban farmer working an ox is not Edgardo

I find Edgardo plowing with his assigned steel-tracked Russian tractor,

which must be pull-started by one of the few vehicles here with a functioning

battery. The red, open cab is roofed with empty Dutch Desire potato

sacks. Cuba imports this brand and Canadian potatoes as seed.

We bounce over rough earth while flights of herons glide down behind

Edgardo on the newly formed rows. The "farmers' friends" line

up like snow-white sentries surveying for mice, which they devour.

After a couple hours plowing, we stop to replace a broken bolt. It takes

another driver an hour to fetch one, all the while the motor is wasting

gasoline because Edgardo is worried he can't get it started again if

he shuts it off.

" I like the co-operative idea," Edgardo says. "We feel

more connected to the soil, to our product. We eat our own produce.

But there are still problems of discipline, bureaucratic slowness and

lack of sufficient resources.

" The revolution has been too generous and too paternalistic. We've

got to learn to produce what we need to, what we should," the Angola

war veteran muses. "Too many people are here only for the material

benefits, like soap and 15 packs of cigarettes a month", compared

to only four on the ration card.

Edgardo gazes off into the savana. One half-expects giraffes to appear

through the semi-tropical grassland. The only animals here, however,

are oxen. The flat land is dotted with avenues of stately royal palms

swaying splendprously erect.

A job for blue jeans

I walk over to my favorite banana jungle and talk with Noel Perez.

Just 17 years old, Noel moved here from his parents' comfortable home

outside Havana six months ago. He tells me why.

" I decided to work in agriculture to help produce the nation's

food, and for my own independence. I also earn more here than at my

last city job. I am saving to buy blue jeans. Then I can look smart

and go out dancing," Noel says, his eyes sparkling.

There is no longer guaranteed adequate clothing on the rations. It will

take Noel all his earnings over four months to buy his imported "dream

pants", which he will probably buy on the black market. But Noel

doesn't care. He looks forward to impressing his friends and, perhaps,

a girl.

Noel associates with other youths recently moved here. They stop work

when they want and sometimes sneak a drink of moonshine rum amidst the

plantation's shadows.

Near where Noel is spreading chemical fertilizer are one hundred 12

to 15-year olds picking weeds and pulling up carrots, just like Noel

did for one month each year of junior high school. The study and work

program, initiated shortly after the Revolutionary victory, still aims

to teach youth where their food comes from, and give them a sense of

identity with workers. The kids also enjoy the freedom of being away

from home and the social life at their rural school close to GIA-2.

Zestful grandmother farmer

I find Guillermina in another part of the banana plantation brushing

dried leaves away from the microjet tubings with her machete blade.

This zestful grandmother moves at a rapid pace, pausing sporadically

to secure or replace a broken sprinkler tip and cut dried parts of the

trunk leaves.

Guillermina and Edgardo were raised on farms and are glad to be back

in the fields. She recounts her past during breaks, which she liberally

takes.

" I was born in the east, alongside Cuba's tallest mountain, Turquino.

My father was a peasant, a strong man who fathered 22 or 23 children;

17 by my mother. He went to the mountains to fight with Fidel,"

she says proudly.

"The revolution gave me everything. Without Fidel I don't know

what would have happened. He unites us. I wish the United States would

stop its blockade and conduct their own revolution like ours, and then

we could all live fraternally," she dreams aloud.

"My kids are grown now. One has a baby. So I decided to seek adventure,

to start anew. We grandparents left our house to our children. This

way we can help the nation get more food, and we can earn more money

and get our own house here."

When the state devised the self-sufficiency Food Plan, it announced

that it would build 44 communities in Havana province, providing 12,000

residences to the farm-workers, plus thousands more elsewhere in the

countryside. The government knew that petroleum to run construction

vehicles and machinery would be scarce but with typical Cuban optimism

it embellished on real possibilities. The gap between desire and reality

resulted in many volunteer workers unwilling returning to their city

homes and jobs. Two years after the planned deadline not one community

had been completed. Only 50 residences had been finished in this province,

of the 12,000 announced, and 7,000 in other provinces.

A small, two-story building stands within sight of the dining hall,

the first six flats out of the 400 promised at Jose A. Fernandez UBPC.

A genuinely elected workers' commission decided on the six "most

distinguished workers" from 40 applicants for the flats. The commission's

proposal was voted on by the entire workers' assembly.

Mileydis Casanova, a 28-year old mother and wife of another cooperativist,

is the proud owner of one of the more or less attractive, three-bedroom

apartments. Her husband, 30 year-old Rolando Fajardo, was often elected

as one of the most distinguished. The terms for buying the house are

extremely liberal. The two pay a combined ten percent of their wages

for 12 years. As long as they stay on this farm the house is theirs.

Once the last payment is made, the house is theirs regardless of where

they work. The state also sells them furniture, a refrigerator and a

small kerosene-burning, two-plate stove all at cost and paid for on

time plan. These are the normal terms for new housing going up in the

farmlands. In a few special cases, there are no costs to the workers

if they stay on and produce well. When there are house payments, they

normally range from 10 to 20 years. The state, as in all housing construction

and sales, takes no profit, but only recuperates the actual construction

costs.

Edgardo and Guillermina hope to be among those homeowners soon, but

founding members of the contingent have preference.

At noon, Edgardo and Guillermina eat a basic hot lunch together and

chat with me.

"We are one culture with one identity," Guillermina explains

when questioned if race is an issue in Cuba. Her complexion matches

her man's cinnamon-colored face, which is topped with kinky black hair.

" Black Cubans, or mulattos, do not identify much with blacks in

other countries. We have come a long, long way from the days of my parents.

They told me how they were treated before the revolution. My mother

was a maid for a rich family for a while; my father a chauffeur. They

couldn't do many of things or go to many of the places that whites could.

Today, it would never occur to any of us that we couldn't do this or

that or live here or there because of differences in color. Racism no

longer exists, not in practice."

While blacks are not discriminated against, Cuban women have not yet

gained full equality despite constitutional guarantees. Guillermina

recently experienced this dichotomy when a male co-worker suggested

that she take over the important responsibility of running the water

pump he had been charged with. She was pleased by his confidence but

the UBPC leadership turned her down on the grounds that it wasn't "women?s

work". The all-male executive was concerned that constantly working

in water would harm "womens' works", especially during menstruation.

The camp doctor and nurse, both women in their twenties, considered

that notion to be "an old wives' tale". However neither they

nor the women's brigade leader demanded any changes because, they said,

"No woman had insisted on her equal rights".

That evening Guillermina changed from sweaty work clothes into a white,

flowered dress and plastic decoration in her natty black hair. She was

going out to dinner. "Out" was just 25 meters from her cubicle

to the dinning hall. She sat with a dozen men, all chosen by their brigades

as the distinguished workers for the past two-week period. Edgardo was

not with his wife as he had been chosen before.

The distinguished workers ate at table-clothed tables. They had the

general dinner of rice and beans, sweet potato and thin soup, plus chicken

for the occasion. The expected rum and desert were absent, however,

and food preparation lacked "a loving touch", Guillermina

lamented.

Guillermina and Edgardo spend much of their free time watching TV or

playing checkers. He is also a good chess player, and she likes to smack

a volley ball with men and a few other scrappy women. The couple's sex

life has suffered since arriving at the co-operative. The contingent

rules against chatting in each other's rooms had been relaxed but cohabitating

at the camp was still forbidden on pain of expulsion.

" It's uncomfortable without our normal sex life," Edgardo

says timidly, "but I won't take my woman down on the ground or

in one of those concrete water-pump platforms like many do. I feel it

demeans the woman and the act of love-making."

They prefer to wait for their three-day passes every second weekend.

Then they travel to Old Havana where they can be alone in a relative's

apartment. They sometimes miss those weekends, however, because they

often choose to work extra weekends for the pay and because transportation

is so discouraging.

Guillermina, though, feels that, "Waiting too long is just too

much. Sometimes I look at Edgardo and say, 'How long can a woman wait?'"

Entwined in each others arms, Guillermina and Edgardo huddle under a

blanket to fend off winter's wind wheezing through un-shuttered port-like

window holes. Alongside others, the couple watch the Sunday matinee

movie on TV, "Memories of the Invisible Man".

BATTLE FOR FOOD

Third in series

Editor's Note: They read like chapters in a living novel, but Ron

Ridenour's stories in his wonderful series on his experiences as a volunteer

farm worker in Cuba are not fiction. This is the third of his five stories

in this uncompromising series. We appreciate that he does not shy from

describing Cuba's problems and also his warm telling of the personal

and national triumphs of a small nation that continues to stand tall

for its independence and sovereignty. Ron's true stories record the

amazing resilience of Real Cubans who marshal their resources to work

the land, advance the Cuban revolution and survive the brutal U.S. embargo

and collapse of the Soviet Union. Les Blough, Editor

________________________________________

Bill's bicycle whisked through city traffic, mounted the first countryside

hill and glided to La Julia in Batabano municipality.

I cycled the 50 kilometers by noon so intent was I on taking a break

from noisy Havana and the many Yankee T-shirt-clad unconscionable people.

I especially looked forward to revisiting the farm where I had often

volunteered in the first half of the 1990s.

GIA-2 was the state collective (granja) nomenclature before it became

Colonel Mambi Juan Delgado contingente, later changed to the Jos? A

Fern?ndez UBPC (Basic Units of Production Cooperation) cooperative.

Hungry farmers milled before the camp kitchen. Benito, the tall lanky

Microjet drummer, approached me. Microjet was the irrigating system,

hoses fixed in the air or on the ground from which comes a fine spray.

Benito had been a contingent member, who had formed the Microjet band

with other volunteers.

"The Microjets are gone, Ron. I'm the only one remaining. But others

you knew are still here and most have their houses. I'm way down on

the list since I am single. But Edgardo and Guillermina got theirs.

" The camp is improved. We are fewer here now so we can share a

room with only one person instead of six. And we got rid of that fucking

sex restriction. Now we can have a woman in bed," old Benito grinned.

I biked the kilometer to the concrete-block housing compound, which

I witnessed when the first four houses were under construction. As I

gazed at the identical grey structures, a woman walked out of one. Despite

her sombrero, I recognized the muscular Guillermina Montero. Her face

lit up when she saw me. After embracing, we walked into her house to

see her husband, Edgardo Rochet.

Most workers have their own houses now, and those who have no longer

eat at the camp cafeteria. If they do eat there, a meal costs 50 centavos.

Guillermina and Edgardo insisted I stay with them. They have plenty

of space: four rooms, bathroom and kitchen. Since they live alone, one

room is used to store fresh harvested foods and three unused bicycles,

all lacking tires and tubes, "which cannot be found", lamented

Edgardo.

Their kitchen is charred black from an accident with the kerosene cooking

apparatus.

" We should use gas but it is not as available as is kerosene.

We are all to get the new electric plates this month, and then I'll

`find´ some paint to brighten up the kitchen," Edgardo said.

"The state says it will be making refrigerators available to us

also," interjected Guillermina enthusiastically. "We haven't

had one for years since ours broke down and there were no parts."

The bathroom light burns constantly because of a broken fixture, which

will soon be replaced with the new energy-saving filaments and bulbs.

The sink is broken. More often than not there is no running water for

showering or flushing the toilet. Buckets are kept filled for both functions.

The residential compound gets its water from the well at the nearby

countryside school, but there are no set times for water flow. Since

many of the couples both work, it is often a house-wife neighbor who

fills up empty buckets for others.

The living room is the centre of attention, because of the Chinese Atec-Panda

television set, which Guillermina "won" for being voted destacada

(distinguished) worker many times. She is paying half price (4000

pesos) on a three-year time plan without interest. Her average wage

is 500 pesos a month, which supplements her 262-peso retirement. Guillermina

retired last year. At 56, she is the oldest woman worker.

" I like to work and helping out the banana plantation crews, plus

we put away a little extra for some future event," the broad-faced

woman said, showing youthful white teeth. After lunch, she returned

to her bananas.

" Now, that we have specific work responsibilities, I've decided

to take the afternoon off. I'm caught up with weeding our papayas,"

explained Edgardo.

He wanted to talk with me while cleaning house and preparing for dinner.

Edgardo, now 50 years old gets 700 pesos monthly. These wages are advances

based upon the previous year's income. The crews earn according to the

product results they cultivate. All workers spend some time on the libreta

(rations) crops like potatoes plus their own designated crops.

At the end of each season, sales are divided amongst the workers after

the cooperative takes its cut for maintenance, administration and new

investments. Last year, Edgardo earned 8000 pesos over the advance monthly

wage. Workers in the more demanding guayaba fruit plantation earned

twice that. Some crops require less work and bring in less income.

" We can feel the differences, Ron. We are more comfortable since

share-profiting was introduced and since we got our house, in 1997.

We're earning three times what we did when you were here. We pay a pittance

for the house until we own it outright [they can't be thrown out by

law], and nothing for gas, water or electricity.

" Of course, not all is roses. They didn't come near their promise

of housing construction and we still don't have more say running things

but the system is more open. So I decided to join the party. I'm now

a militant."

Guillermina came in with a small chicken in one hand and a bottle of

my name in the other. She had taken off work early to buy her favorite

meat at 60 pesos, and a cheap rum at 30 pesos.

" We celebrate your return, Ron. Cheers," and we downed a

tingling shot.

Guillermina caressed our dinner with one large and callused hand. Its

eyes closed peacefully and she twisted its neck in one motion. Not a

pip. It took Guillermina just minutes to pluck and cut up the chicken.

As it simmered in a pan, and as the sweet potatoes, rice and beans were

cooking?which Edgardo had prepared along with a fresh green and tomato

salad?the loving couple took a bucket bath together. Edgardo had heated

the water with a Chinese spiral electrical heater.

Dinner was delicious and festive.

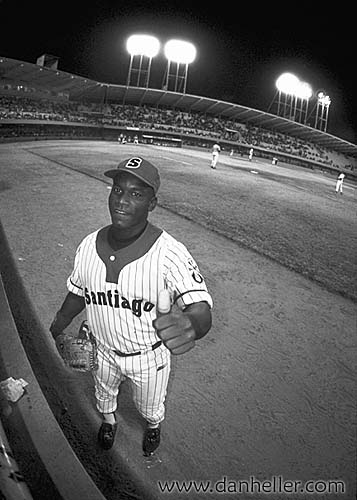

My hosts' home-town baseball team and a Havana club were starting a

three-game series, which must be seen. After the Walt Disney cultural

imperialism hour, we watched the game on their 101-channel television

set. Only Cuba's five stations can be seen. Five of the 23 families

in this compound have TV sets so several neighbors roared or moaned

with us.

Hands in soil

Grunting pig, crowing cock, buzzing mosquito, child crying! You name

the noise and it penetrates through wood-slatted windows that can't

be shut tightly and through the porous concrete structure. I rose from

the narrow cot and thin mattress and stepped into the acrid bathroom.

Coffee and a plain hard bun for breakfast, and we were all but ready

to start the work day. But not before filing sharp my 40-cm long banana

machete, Guillermina's knife and Edgardo's heavy hoe.

Entering the mature plantation in the early morning dew is a venerate

experience. The shadowy silence and fresh moisture embraces and comforts.

Under the tall fruit banana and shorter burro banana trees, the sun

does not penetrate to human height and fronds protect one from rain.

All is green and tranquil.

This was my experience again, just as I described it a dozen years ago

when Guillermina and I worked the fruit jungle. Today, Guillermina works

in the larger of two banana plantations with 54,000 trees, divided into

12 sections. One worker is responsible for each plot of some 4,500 fruit-bearing

plants, but they often work in pairs or small groups.

GIA-2 is still its common name but the cooperative has fewer bananas

than when it encompassed 900 hectares. All UBPCs were reduced in size

so that fewer workers could better tackle the tasks. Much time was lost

when the land was so vast and many of the 300 workers had to walk so

long to and from work. GIA-2 split into four UBPCs. This one of 192

hectares is tilled by 126 workers.

Guillermina introduced me to fellow workers as "un cubano mas"

(just one more Cuban), making me blush with pride.

Today, we were to cut dried ends of the long fronds before the trees

grew over our reach, and the outer layer of the trunk, the yagua, behind

which thrives a little green frog. This cute, gentle animal unintentionally

causes fright in most Cuban women and some men. Even "superwoman"

Guillermina gives a yelp and takes a step back upon seeing one. So,

men usually cut the yagua.

Stooping and slashing round the plant, stepping to the next, stooping

and slashing, simultaneously swatting mosquitoes and mites. That's the

routine but it doesn?t need to be boring. We are our own bosses, in

part, and can stop when we want, chat when we wish, or exchange tasks.

Lunch at the cafeteria was tasty and nourishing but some of the old

timers reminded me that when all 300 workers lived in the camp, instead

of 46 now, the meals were richer. There is never beef and almost never

fish. Cuba's fishing fleet has been drastically reduced. Yet now they

have more variety of vegetables and fruits, because they have diversified

their crops.

The topic of food is more troublesome to camp dwellers than is camp

cleanliness, including toilet-shower hygiene. The facilities have deteriorated.

There are no lights; fixtures are broken and all bulbs burnt or stolen.

Only two showers function and must be alternately shared by men and

women. Plumbing is worse: only four clothes-washer sinks work; "toilets"

are still holes in the ground with soiled newspapers beside them.

After lunch, I was shown the cooperative's biggest challenge: grape

growing. A Spanish wine growing investor imported thousands of young

plants. Under his instructions, workers fastened vines between three

wires stretched over hundreds of posts. Grapes require intensive labor:

constant watering, stem cutting and lots of weeding.

They have sown peppers between the 500 rows containing 37,000 grape

vines.

Thirty thousand papayas have been planted behind the grapes. The farm

administration bought seeds from private farmers for the first crop

and they hope to use their own seeds for the next planting. Digging

holes in the hard red earth is arduous ?man?s work?. As we hack, women

unload 6,000 new plants from a borrowed oxen cart. (They used to have

their own oxen but sold them to buy tractors.) Plants are then placed

in holes, which once contained other papaya plants that died from lack

of proper planting and inadequate irrigation.

Mirta, yet another member from Santiago de Cuba, complains of the needless

loss.

"The field director neglected to see to it that the earth was properly

watered and fertilized before he ordered us to rush the planting."

Why didn't you say so?

" Ah, what good does complaining do?" she retorts, her eyes

rolling.

" We have complained about some things," added her partner,

"like the ridiculous guard duty. We work six days a week and half-day

every other Sunday. On top of that, we must conduct four monthly 12-hour

night shifts `guarding´ the fields. But we cannot be armed while

the thieves may be. They are prepared to come in the steal of the night

and take crops without our seeing them, or if we do, so what. What can

we do to stop them?"

Night guarding, however, is a condition of membership, these workers

say. The response to earlier protests was: guard duty or dismissal.

Later, I spoke with an older man whose full-time job is to guard an

abandoned resident shelter. He lives alone in one of the run-down shacks

on 225 pesos a month. There is no electricity or running water. His

prepared meals are delivered to him.

"You know us Cubans. Without a guard, every bit of concrete left

would be broken up and hauled off. They say they will rebuild this place

one day for residences. What do I know?" he shrugged.

General assembly democracy

After dinner, most of members attended the monthly general assembly

in which evaluations are made and plans laid. The UBPC director, Matias

Cabrera, was appointed by the regional UBPC firm three years ago to

replace a negligent leadership, which involved some fraud. Matias, now

40, had been a farm worker since youth. He opened the meeting with the

accountant's financial report: no losses in three years; monthly profit

sharing is above average in last period at 125 pesos; our sales, especially

to tourist centers, assure us profit, and we are regularly paying off

our 2.2 million debt; cafeteria is operating at a loss, each meal costs

thrice what camp residents pay: 60 pesos monthly.

There were no questions or comments.

Then Matias delineated problems and plans in a monologue stream.

" We have not received sufficient boots but more are expected;

we have problems with our irrigation system and this is acute, especially

avocados; we are replacing the lost papayas.

"Thirty-one members are behind in paying their union dues, including

some leaders. This shows a lack of respect. There were 29 departures

in December; four firings: 2 for thievery, 2 for indiscipline and disorderly

drunkenness; the remainder decided to quit.

" Camp discipline is faulty and the grounds are dirty. The cafeteria

lacks some essentials. Since we do not foresee enough housing construction

in the near future, I am proposing that the camp be legalized as permanent

residences for each person or couple without a home and installed with

cooking facilities. In this way, we can close the cafeteria and everyone

will have a home.

" From now on, fines will be levied for those who do not clean

their area adequately. There are 15 undocumented workers. If they do

not get their papers in order within a week, they are dismissed. The

administration is responsible and would be required to pay a penalty.

Beginning tomorrow all workers are required to participate in potato

weeding.

" That is all. Are there any questions or comments?"

Only one man spoke. He asked why they didn't buy sufficient papaya plants

to replace the loss. Matias replied that there were not enough funds

and they must now concentrate on potatoes.

After the rather dry assembly, I milled about outside with some long-faced

members. People were unhappy with the constant turn-over of members,

with the fines imposed for untidiness, and Matias' manner of addressing

them as underlings.

Mirta and her crew said that they didn't speak up because, "it

would not change anything." Edgardo and others said that the promises

of elections and worker decision-making exist only on paper. Young Alejandro,

a recent member, also from Santiago and known as the leading jodedor

(clownish joker) viewed it differently.

" I see no need to criticize or rebel. We take orders, because

we know the leaders want to go forward for and with us. They are little

mangoes (meaning good people)."

Potato weeding

We walked directly from breakfast to the fields. The matutino

(morning meeting) is no longer a cooperative feature, discarded as a

"waste of time"-a radical departure from the earlier attitude

of without a matutino there is no cooperative. Several scores

of hectares with rows half-a-kilometer long, each with about 1,500 potato

plants and tens of thousands of choking weeds. This is not a pleasant

sight. No one looks forward to work today and the coming days it will

take to hack and pull up weeds.

Mild-mannered Alex, the production chief, and Juan, potato crew leader,

led us into the first rows. They showed me how to hoe the weeds without

getting too close to the plants. The problem is that to avoid cutting

potatoes one must stoop over most plants to pull out the weeds growing

amidst the plants themselves. I experienced that to do a thorough job

of weeding requires much more time and painful stooping than the majority

were prepared to offer. Most hack the weeds without getting down to

the roots, and the amount of stooping to pick out weeds that can not

be hoed is not commensurate with the amount of weeds.

Hacking, stooping, hacking and stooping. My head ticked with figures.

How many rows, potatoes, weeds, how many man/woman hours? I came up

with some three million potato plants. And they should cultivate twice

in the season. So there must be two campaigns with most of the members

participating.

Alex realized that the work is so tedious and takes so many days that

he does not conduct quality control thoroughly.

Juan showed me their use of biological control against pests. The ladybug

eats the bigger bad guys, cinche. Juan said that most farmers

are using as many ecological methods of farming as possible. State instructions

and propaganda have greatly risen the national consciousness about the

worth of organic versus chemical.

" The only problem," Alex says, "is if the good bugs

get overwhelmed by the bad ones and can't reverse their growth. If a

plague sets in then we must use chemical pesticides. The problem with

that is once they are used it takes a long time for the poison to disappear

so that we can go back to biological control. In the five years I've

been here we've used chemicals just two or three times. We can't be

completely ecological. Our priority is to put enough food on everybody's

table and, hopefully, without having to use precious valuta to import

it."

Farming Structures

All farmers are required to grow and sell basic products to the state,

in order to assure everyone rationed goods at subsidized prices, the

libreta, and at less subsidized prices on the state farm markets,

set up in 1994 to compete with and undersell the supply-demand farmer

markets.

At first, private farmers supplied most of the goods but at prices few

could afford. Soon state cooperative farmers began selling products

at cost+ prices after meeting libreta commitments. The army,

which produces much of its own food, joined in the competition with

its EJT soldier-farmers.

Private farmers are still entitled to own up to 65 hectares of land

but there are only a few thousand unaffiliated farmers remaining. In

the 1960s, most independents and cooperatives created the National Association

of Small Farmers (ANAP) to represent them before the state. In the 1990s,

ANAP set up a new organization for mutual financial benefit, CCS (Credit

and Service Cooperatives).

ANAP farmers now produce 60% of the nation's root and green vegetables

and grains, 60% of its pork, and ANAP is the major producer of tobacco,

livestock, fruits and coffee. It is especially CCS farmers who earn

the greatest valuta profits from Cuba's renowned cigars and coffee.

The state collectives had produced practically all the sugar and rice.

Sugar is now produced mainly by the UBPCs (90%), which is also a major

producer of green and root vegetables and fruits.

Most rice is produced by yet another form of farming: the Urban Truck

Farms (UTFs). The UTFs are tilled by family units and some full-time

city farmers, who utilize organic intensive growing methods. They grow

the best green vegetables, herbs and condiments.

UBPCs now till about half the nation's soil, double what they had in

1995. ANAP's 300,000 members till approximately 35% of the cultivated

land (25% of total agricultural lands); the EJT about 8%; some old granjas

still exist and till about 8% of the land. These farm workers now have

better wages and some profit-sharing. They cultivate some vegetables

but mainly citrus fruits. The remainder of produce comes from the UTFs,

which includes self-consumption and market sales.

There are over one million farmers of all kinds. This is 21% of Cuba's

4.6 million workers (service=64%, industry=14%). No farm worker lives

only on wages any longer. Profit-sharing has taken over and has satisfied

a basic demand.

These changes have also improved the state budget. Subsidization of

agriculture has decreased significantly, from 54% in the 1990s to 20%

today.

Dr. Santiago Rodriguez Castellon, agricultural economist at Havana University's

Cuban Economic Studies Centre (CEEC), provided facts and figures and

described changes.

" The reduction of subsidization is one of our greatest achievements.

Another is the 50% increase of all vegetables in the last three years.

We now produce 60% of our food, up 220% from a decade ago. We are not

long from when the Special Period will be concluded."

There is yet a ways to go, Dr. Rodriguez admits. "It had been predicted

that UBPCs would take over all granja lands and that all would be profitable.

While they have doubled production, only half are profitable; others

must rely on state subsidies and credits.

" Not nearly as many housing units have been built as promised.

Many leave UBPCs because they must live in cramped collective compounds.

The longer established private cooperatives are more attractive. The

few granjas left are still too dependent on the state and lack many

resources. Moreover, poor work habits inherited from before the Special

Period have not been eradicated."

The economist lamented that the UBPCs have not matured to the point

where workers elect their own leadership, in most cases. "The objective

of autonomy is still extant, but it is difficult to define and separate

where the state stops and the cooperative autonomy process starts. The

old centralism, however, has been broken."

It was the state's top leadership, which took the initiative to combat,

what many call, "revolutionary paternalism".

Director Matias

Matias' house looks like Edgardo-Guillermina's. The key difference is

that he has DVD and other modern entertainment technology, which attracts

neighbors. They come to borrow salt or sugar; some stay to watch TV

and drink coffee, which his young wife gladly serves. Matias is not

preoccupied with critical questions posed.

" Membership turn-over is not a problem. There are always more

seeking work than leave. Those who leave don't want to work hard. Too

many Cubans are spoiled and lack consciousness. And we do have a stable

group of 78 workers, mainly those who have housing."

What about the papaya crop?

" The original planting was faulty, a lack of consciousness again.

Sure, I have enough money to buy the necessary plants but I didn't want

to tell the assembly this. They must concentrate on potatoes now."

Lying for convenience is not viewed culturally as a "sin"

or wrong, especially if the intention is well meant.

Does his leadership style turn people away?

" Look who's in my house? Everyday it is like this, a dozen or

more people pass in and out. Some may not like it when I'm precise.

But they can't deny the facts: we have had a profit each year I've been

here; most weeds get removed; we've made several million peso investments

in the best paying crops: avocados, papayas, mangoes, guayaba, and the

wine grapes, which is a long-term investment."

Matias may only receive a fixed monthly salary of 500 pesos but some

workers point out that he gets shares based upon their production, has

the only house in the compound with a freezer, and has several rice

cookers plus the entertainment apparatuses, which many enjoy.

FROM HARVEST TO TABLE

Fourth in Series

When I worked in agriculture in the early 1990s, one of the greatest

problems was the distribution system. The December 1993 national assembly

sessions included an alimentary report by Candido Palmero, former head

of agricultural contingents. He said that the contingents and the new

cooperative UBPCs could guarantee their production goals but he couldn't

guarantee that "you will eat all harvested crops, because we don't

have our own trucks to distribute goods."

Candido considered the state centralized food distribution centers,

Acopio, a disaster!

Although Fidel and other state leaders expressed interest in changing

the system and distributing directly to local markets, there remains

much to be done. In contrast to then, however, other forms of distribution

are allowed. For example, most ANAP cooperatives have converted to the

Credit and Service Cooperative (CCS), which own and share farm equipment,

and many CCSs own their own distribution trucks, a significant advantage

over most state cooperatives.

Most private producers distribute directly to designated farmers markets,

but they must buy gasoline and parts in the convertible currency (cucs).

If they distribute their own crops, they also lose precious time from

the fields or they must employ drivers and (illegally) vendors. Nevertheless,

direct distribution to market places is common fare for 25,000 individual

farmers, for nearly 2000 CCSs and the remaining 750 Agricultural Production

Cooperatives (CPAs), and the farmer-soldier EJT. Even a few profitable

UBPCs and granjas have sufficient funds to buy vehicles and distribute

directly to markets, or they set up stands where people can buy those

products remaining after sales to the state.

Distribution and Investigative Journalism

Matias Cabrera did not see any problem with the traditional Acopio system.

" Improvements have occurred since your time. Both producers and

distributors are better in advising one another concerning times of

harvest, how much shall be collected and what days the trucks will arrive,"

the UBPC farm director told me.

"We get three different prices for our products, one for the

libreta rations, another for the state controlled farm markets,

and a third from the tourist hotels. The Acopio collects and distributes

more exactly.

" Thievery of our products is prevented because a farmer rides

in the trucks. He observes what is delivered where and sees that the

correct payment is noted. Control is better."

In February 2006, the Communist party newspaper, "Granma",

conducted an unusually critical investigative series about problems

in agriculture, farm markets and distribution. "Granma" confronted

distribution problems, which Matias apparently oversaw, when it interviewed

the Acopios national leader, Frank Castaneda Santalla.

" We recognize that our transportation is deteriorated. Four hundred

trucks are inactive for lack of parts and repairs. We have 1,200 trucks

for the whole country, and only 60% are active. The Ministry of Agriculture

has recently invested funds in tires and batteries, in order to reactivate

172 trucks and 92 trailers. Most of our trucks are from the old socialist

Europe. They have 20 years or more of use and consume enormous amounts

of fuel."

Acopios have too few front line employees

" We have 17,000 employees, but 40% are administrators and bureaucrats.

We propose to reduce them by fifty percent."

Castaneda added that Acopio workers need better wages and an improved

image.

Both Castaneda and Vice-Minister of Agriculture Juan Perez Lamas, whom

"Granma" also interviewed, maintain that the chief cause of

insufficient foodstuffs is not with Acopio distribution weakness, however,

but lays in insufficient production.

Castaneda said that illegal distribution intermediaries would disappear

if farmers were motivated to produce more, if they would be content,

"to live on the income from their harvests and not motivated to

sell at higher prices."

In "Granma's" February 21 article, Ciego de Avila province

Acopio leader, Giuvel Rodriguez Rivero, contradicted Castaneda and Perez.

" The distribution of agricultural products is an old challenge,

which has not been totally solved. The principal problem is lack of

transport," he said.

" I am of the opinion that the Acopio is not serious. It does not

comply with its commitments, and should be more flexible in ratifying

sowing (and harvest) plans exactly. And when the Acopio delays collecting

harvests, they are sold to whoever appears. Is this not an illegality?

I won't deny it (but in this way) the harvests are not lost. We know

there are receptive stomachs.

In another "Granma" interview, ANAP's president, Orlando Lugo

Fonte, who is a member of the State Council, offered a frank portrayal

of problems: contractual agreements often not made or completed, lack

of packaging causing loss of "much food harvested", and lack

of weights where crops are delivered at the Acopios.

" There are very few animal weights so their weight is estimated

by a functionary; and there are too few weights at farmer markets. Another

major problem for farmers is late payment of delivered crops by the

ministries of agricultural and sugar.

"Ministry functionaries are often undisciplined in setting prices

in time for farmers to buy seed. And the ministries buy products at

different prices based on quality. But in most markets, the sellers

do not make quality distinctions in sale prices. Farmers must also pay

29% of the product price for distribution and commercialization,"

Lugo explained.

Sometimes farmers' income does not meet their costs

Lugo said that the more expensive supply-demand farmer markets are often

supplied by self-employed intermediaries. They usually drive to the

fields and buy products directly from farmers. And there is less control

in these markets, including veterinary certificates, than in the state-run

markets, where prices are set by the state and quality checks are made

by inspectors.

" Granma's" interview with Vice-Minister Perez focused on

food marketing and common complaints of high food prices. Perez, a former

farmer, offered the following figures: each person has a monthly need

of 30 pounds of all forms of vegetables, grains and fruits, requiring

2.5 million tons. Another 2.5 million tons are produced for food consumption

outside the home, restaurants, tourist centers, hospitals, canned goods

for export.

Seventy percent of household foodstuff is sold in the state's 13,800

free markets. In addition, there are 400 small organic food stands where

prices are often arbitrarily set.

" Granma" asked the vice-minister why prices are often arbitrarily

established, why payments are late, and why farmers often end up on

the short end of the stick.

" We are strengthening the Acopios...We make imprecise estimates

of harvests and this results in inadequate control in the organization

of packing and transportation?We have made up for most back payments

and this problem should disappear."

According to Acopio leader Castaneda, the Acopios lack at least 6,000

scales

Regarding the lack of weighing products, Perez simply admitted that

this occurs. Perez added that there is still a scarcity of means of

production and seeds to meet all farmers' needs. Many types of seeds

are sold to farmers at subsidized prices. However, the state can not

provide sufficient fertilization, so what there is, is sold to the highest

yielding farmers.

Nevertheless, farmers receive more resources than before: modern irrigation

technology (for some farms), using less fuel and more electricity, and

there are more tractors and oxen than before the special period.

" But we lack work clothing, boots, machetes and sharpening files,

tractor parts and tires...We deal out to the best producers, no type

of farmer is discriminated against. All farmers get free technical advice

from state institutions," Perez continued.

" Our biggest challenge is to reduce high prices, so we must achieve

greater production."